By George Lott, Jr.

The following is an article published in the June 1964 edition of World Tennis magazine by International Tennis Hall of Fame member George Lott on his U.S. Davis Cup teammate Sidney Wood, one of the most fascinating figures in the history of tennis, as described in the book “The Wimbledon Final That Never Was…And Other Tennis Tales From A By-Gone Era” (available here: https://www.amazon.com/dp/0942257847/ref=cm_sw_r_tw_dp_x_PFQyybYRVBMSJ

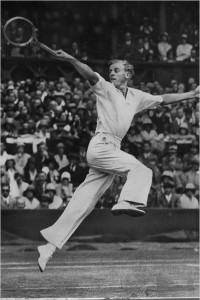

When you watched Sidney Wood play you got the impression that you were seeing a genius at work. He went about the match as would a mathematician while executing strokes with skill and dexterity. His main strength was lovely, deadly accurate backhand with he could thread the needle. The first serve was big and deceptive, but the second twist was a bit uncertain. His forehand was a constant experiment but never a weak stroke when compared to his superb backhand. He was a deadly volleyer with a strong overhead. Put this combination together, then add one of the finest brains the game has seen, plus a great competitive spirit, and you have Sidney B. Wood, Jr.

My first experience with Sid was at Southampton in a two out of three set quarterfinal. I led 5-1 and 40-love in the third set, then 5-3 and 40-love. I had a total of nine match points – and lost. This is remarkable enough of itself, but those nine points were from another planet: I attacked his strength and came to net, and each time covered the crosscourt return. Each time he beat me with a down-the-line passing shot. Now you would think that after three or four of these parries I would do something different, but each time I came in I told myself he would not still go for it, that he would not think I was not that stupid; but there was not one player in a thousand who would think the way he did, let alone make those nine straight backhand passing shots!

He had a great tournament that week, beating Frank Shields, who’d scored a major upset against Big Bill Tilden, the day before, in five sets after losing the first two, and doing exactly the same thing against Wilmer Allison, fresh from a win over the great Henri Cochet in the Wimbledon semis. Sid was a real Silky Sullivan – not only that week but in every match he played.

Sidney holds records which are likely to hold up against the onslaughts of time. He won the Arizona men’s State Championship at fourteen and, at fifteen, was the youngest ever to compete at Wimbledon, meeting previous year’s winner, Rene Lacoste, on the Centre Court. He had qualified by gaining the third round at the French, and he is the only Wimbledon champion to win his crown without playing a point, when an injured Frank Shields was forced to default in the finals (later to lose a friendship pact playoff to Sid at a Queens Club finals).

When all 100 pounds of Sid first appeared on the adult tennis scene, he had two at least two strikes against him: he had survived a seriously ill, often bedridden pre-teenage life, and he was the nephew of both Watson Washburn, a top five ranking player and Julian S. (Myke) Myrick, better known as the Czar of American tennis, who ruled much as Stalin dominated Russia. When Myke was not the president of the USLTA, he was the power behind the throne. However, Sid made his own way and the Czar never lifted a hand to help him unduly. The only evidence of their relationship was the smile on Myke’s face when Sid won something, which was plenty. It didn’t take long for the players to accept Sid for the fine player and gentleman that he was. I cannot recall a single instance in which Sid was engaged in a rhubarb on the court. In those there were no awards for sportsmanship; if there had been, Sid would have been at top of the list when the votes were counted.