Former New York City Mayor David Dinkins died Monday at the age of 93. His passing is mourned by not only many New Yorkers and people involved in politics but also many people in the world of tennis as Dinkins was one of the biggest supporters and fans of the sport in the United States.

In 2017, author Judy Aydelott featured Mayor Dinkins in a chapter in her book “Sport of a Lifetime: Enduring Personal Stories From Tennis” (published by New Chapter Press for sale and download here: https://www.amazon.com/dp/1937559645/ref=cm_sw_r_tw_dp_x_tvqVFb4BTEJPJ)) Aydelott provides a mini biography of Dinkins in her chapter, detailing his life growing up in Harlem where his childhood resembled scenes from the TV show “Little Rascals,” to his persistent effort to join the U.S. Marines, to meeting his wife Joyce at Howard University, to his introduction to politics that concluded with him becoming the first black Mayor in the history of New York City. Aydelott, of course, writes of the Mayor’s love of tennis. An excerpt from Aydelott’s book is found below.

Perhaps the biggest achievement by Dinkins as Mayor was when he successfully negotiated to keep the U.S. Open in New York. Dinkins loved tennis and followed it closely, but more important, he knew that the U.S. Open brought significant revenue to New York City. When upgrades were needed to the USTA National Tennis Center in Flushing Meadows, needing additional city parkland, Dinkins took action to allow the tournament to continue to be upgraded against threats that the tournament could leave New York City.

In 1968, tennis became an “open” sport permitting professional and amateur players to enter tournaments, as was done in golf. Until then, tennis players who played at the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, the most important tennis tournament held in the U.S., had to be amateurs. Amateurs were not allowed to accept prize money. As a result, some of the better players turned “pro” and started their own tournament tour, but their “tour” suffered from little financial backing and scattered organization. Their purses were small. Struggling to make a living, many good players quit; others didn’t even consider a career in tennis unless it was to teach.

When the Open era began, finally, dramatic changes occurred. Amateur and professional players entered the open tournaments, and tennis was elevated to a popular spectator sport. The tennis stadium at the West Side Tennis Club could not accommodate the growing crowds. The United States Tennis Association ultimately decided in 1978 to move the Open to the Singer Bowl built for the 1964 World’s Fair. Renovations were made, and the stadium was renamed the Louis Armstrong Stadium in honor of the world-famous musician Louis Armstrong, who lived nearby.

By the late 1980’s, the U.S. Open had become so successful that the USTA needed to upgrade its facility to keep up with the growth of the event and needed to use more parkland in Flushing Meadow to create a new stadium, now known as Arthur Ashe Stadium. As leverage, the USTA threatened that if they were not allowed to expand its footprint in Flushing Meadow, it might be forced to find another tournament location outside of New York City. Dinkins knew that if the USTA planned to leave New York City, the loss of the U.S. Open would not only be a loss to loyal sports fans but also more importantly, a significant loss in economic impact to New York City.

“People come from all over the world to attend the U.S. Open,” argued Dinkins. “They’re not just local fans who hop in the car or take the subway with the family for a day at Yankee Stadium. The U.S. Open fans bring their families from Europe, Australia, Serbia, Croatia, wherever and stay for a week in our hotels, dine in our restaurants, buy presents to take home. They’re an enormous boost to our economy!”

In spite of these arguments in favor of keeping the Open in New York, Dinkins faced opposition. They believed the project was too costly, one that New York City could ill afford with all its other needs. “However, during negotiations which were handled primarily by Carl Weisbrod on behalf of the city, it became clear that we and the USTA essentially agreed on one critical matter: the New York metropolitan market was too important to lose. Negotiations with the USTA, the ATP (Association of Tennis Professionals), the WTA (Women’s Tennis Association), the FAA, (Federal Aviation Administration), the City Council and other agencies began and went on for more than two years.”

First, the USTA complained that there was not enough land for the project, that the land was on a landfill, that the unions would be difficult, that the expense would be prohibitive and that the infrastructure getting people to and from the location was in terrible shape.

Local residents were opposed to the idea. Located in the Borough of Queens, its President, Claire Shulman, fortunately became a strong supporter and advocate of Dinkins’ plan. She helped appease the objections of Community Board #8, the representative board for the residents in that area. Community Board #8 objected to the loss of the popular park built on the former World’s Fair site used by Latinos, Asians-Americans, African Americans, the poor, and low and middle income residents. One much loved part of the park was a pitch-and-putt golf course. Community Board #8 argued that all those amenities would be lost to a constituency that’s often ignored by the politicians. President Shulman convinced her community of the merits of the new tennis facility and found a way to move the pitch-and-putt to another location.

“Much credit too must go to Claire’s attorney, Nick Garufiss,” added Dinkins.

Another hurdle was what to do about the air traffic. The proposed center was right in the middle of flight paths into and out of LaGuardia Airport. Ivan Lendl, a leading player, said, “We’re outa here if planes fly over our heads.”

Dinkins negotiated with the FAA to find a solution. Finally, the FAA agreed to divert air traffic for the two weeks of the U.S. Open. The USTA wanted an agreement in writing to that effect. The FAA refused. Ultimately, Dinkins agreed that the city would pay a fine, with a cap of $325,000, payable to the USTA if the FAA failed to keep all – every flight – air traffic away from the site. To this day the city has not paid a dime. The FAA kept its word.

Also dicey was the structure of the lease. What would the term of the lease be? Would the city own the stadium and the outside courts or would the USTA? Would the city lease the land to USTA? If so, would the rent be based on gross receipts or net? Would the tennis center be available for use by the city and the public during the 50 weeks a year when not being used for the U.S. Open?

Dinkins knew the problems the city had collecting rent from Yankee Stadium and Shea Stadium based on net proceeds. When the lease is based on net proceeds, the tenant deducts what one might consider unwarranted costs from the gross to lower the net receipts, leaving the city with less than it had anticipated. Dinkins remembered the lesson learned from his father as a young boy: the difference between net and gross. He and his team negotiated a commitment that the U.S. Open would remain at Flushing Meadows for twenty-five years, with rent starting at $400,000 with incremental increases, plus 1% of gross revenues and options to extend the lease to a total of ninety-nine years. The 1% gross revenues included profits from sales of food, clothing, sports paraphernalia, restaurant business and television rights.

Pursuant to the lease agreement, the city retained ownership of the land; the USTA paid for the construction and renovation of all the facilities; the city was responsible for improvements to the Grand Central Parkway, entrances and exits, which were sorely needed – with or without the tennis center.

Dinkins argued that the $150 million spent by the city will “keep the world’s greatest tennis tournament in the world’s greatest city.” Others were less enthusiastic, but Dinkins proved to be right – very right!

Baseball stadiums are generally used 81 days a year. When the Yankees or the Mets make it to the playoffs and the World Series, a few extra days are added. Football stadiums are used even less: one day a week for 9 to 11 weeks a year. This not ‘the’ lease provided that the facility could be used by the public and the city when not hosting the U.S. Open.

The New York City Council was responsible for approving the project, and in 1993, with the election campaign between Dinkins and (Rudy) Guiliani in full swing, pressure on council members to vote against the project was fierce. Ultimately, shortly before the general election in November, the Council voted to approve the project. The timing was tight and Dinkins hoped that if Guiliani won, he would not carry through on his threat to squelch the deal. Guiliani did win the election and brought the issue before the City Council attempting to rescind the lease, but the City Council voted against his proposal.

The new and improved USTA National Tennis Center has generated more annual income to New York City than the Yankees, the Mets, the Knicks and the Rangers combined. Colleges and schools conduct tournaments at the tennis center; tennis instruction is given at the tennis center; courts, fitness facilities and a hospitality center are available to the public for a fee paid to New York City.

Later, Mayor (Mike) Bloomberg, while in office, gave Dinkins the ultimate compliment when he commented that the USTA National Tennis Center, “is the only good athletic sports stadium deal not just in New York but in the country.”

Revenues increase every year. In 1991 revenue totaled $145 million. By 2015, the revenue had grown to more than $750 million according to one study. In addition, 13,000 seasonal workers are employed at the tennis center and in the community during the Open. The U.S. Open has become the best attended sporting event in the world and is broadcast to 188 countries worldwide.

“I love the tournament. I love the sport. I love New York City,” exclaimed Dinkins.

Dinkins made it happen. I’m not sure that Dinkins gets enough credit for this accomplishment, but he doesn’t seek the glory. He’s happy having the plaza in front of the East Gate entrance named “The David Dinkins Circle.” And he is happy to have daily tickets in the President’s Box each year. After his tenure as mayor, Dinkins served as a member of the USTA’s Board of Directors, where he was instrumental in having the facility named the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center, after the phenomenal tennis player, advocate and his good friend.

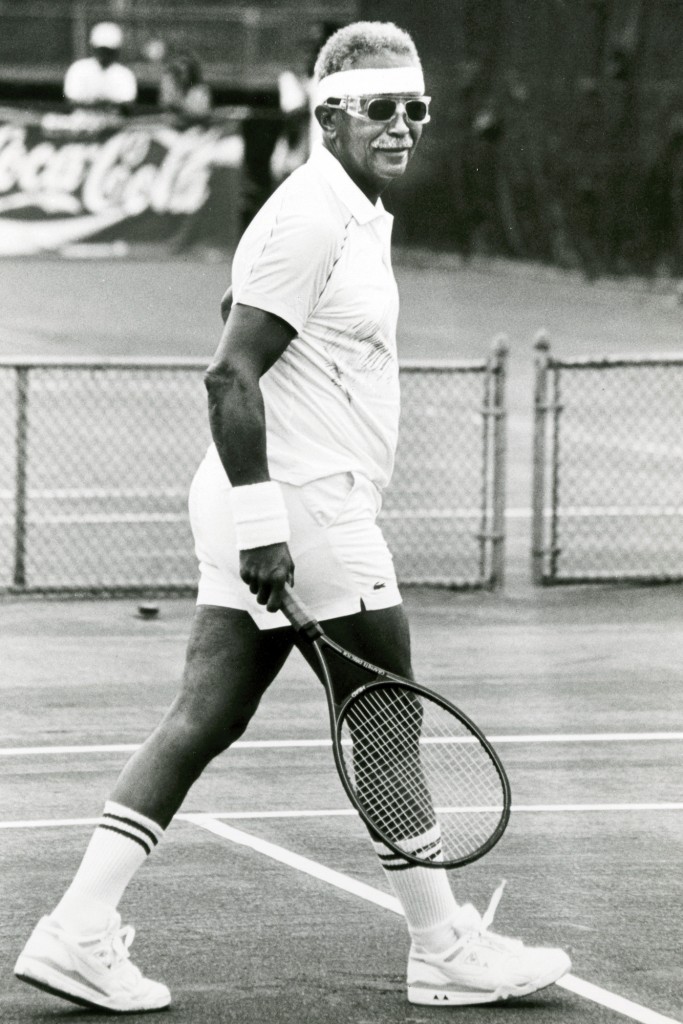

Mayor Dinkins was a late bloomer as far as tennis is concerned, but once he took up the sport, there was no stopping him. As a young boy, he had played some ping pong and when in high school and college he “had messed around with tennis a bit but I had no instruction and no idea how to play the game.”

In 1974, during the tennis boom of the ’70’s, Bill Hayling, the brother of one of Dinkins’ best friends from childhood, put a racquet in Dinkins’ hand. By this time Dinkins was 47 years old, but he had kept himself in pretty good shape over the years and was ready. After that, he played every day, whenever, wherever.

Dinkins joined a black country club in Scotch Plains, New Jersey, at the height of the tennis craze and became a part of the wave of new players in the sport. Since then, many people have given up on tennis because it takes time and effort to get good. But not Dinkins.

Mayor Dinkins came to know Arthur Ashe, one of America’s finest tennis players, benefactor of tennis and gentleman, as both were well-known figures – one in politics, one in tennis – each with similar interests even though a generation apart in age. And they even share the same birthday – July 10th.

“I became very close to Arthur and his wife Jeannie,” said Dinkins “And I was with them when they first met. I think it was the United Negro College Fund that was having a tennis benefit at Madison Square Garden. Part of the festivities was a ‘celebrity’ tennis match between Ron Gault, a former U.S. Justice Department attorney, advisor to Mayor Koch and good friend of mine, and me against Andrew Young, the civil rights activist, Congressman, former Ambassador to the United Nations and Mayor of Atlanta, and Gordon Parks, the famed photographer. I don’t remember who won, but Jeannie, a photographer, was at the event as a guest of Gordon Parks. They were introduced, and the rest is history.”

The Ashes and the Dinkins spent many happy times together. Dinkins cannot say enough about Arthur Ashe and the influence he made on tennis and the world, not only as a marvelous tennis player and gentleman but also as an activist against apartheid and discrimination against blacks.

“I spoke at Arthur’s funeral, and I said, ‘Arthur was a credit to his race – the human race,’” he said.

When Dinkins was struggling to learn the game, Ashe said, “If you want to see what a tennis player should look like, go see Charlie Pasarell.”

Dinkins did one better. He went to Pasarell’s coach, Welby Van Horn, a highly respected tennis coach and former professional player. Van Horn started his coaching career in 1951 when he became the head pro at San Juan Puerto Rico’s new Caribe Hilton tennis facility. There, he coached Charlie Pasarell’s father, also an excellent player and then his son, “Charlito,” who became the top-ranked American player in 1967 and a good friend of Ashe. In the 1970’s, Van Horn had a summer tennis camp at the Choate School in Wallingford, Connecticut and Dinkins attended in 1974 and 1975. He described Van Horn as a “funny fellow.” Van Horn always cautioned his students that “there’s no easy way to learn tennis. Too many players were ‘cats’ and not enough ‘dogs.’ The ‘cats’ were players who ran around the court just trying to get the ball back. The ‘dogs’ were serve-and-vollyers who served well, ran to the net and put the ball away.”

Dinkins gives Van Horn credit for creating his game, though he wished he had a better backhand.

While Dinkins was perfecting his game at the Van Horn tennis camp, Ashe, in the summer of 1975, was playing at Wimbledon. As the No. 6 seed, he made it to the final where he faced Jimmy Connors, the No. 1 seed and heavy favorite, but Ashe took his coach’s advice, “Hit low to Connors’ forehand, give him junk.” Ashe then startled the tennis world, winning 6-1, 6-1, 5-7, 6-4 to become the first black man to win the Wimbledon men’s singles title.

In 1969, Arthur Ashe, Charlie Pasarell and lover-of-tennis and benefactor Sheridan Snyder co-founded the National Junior Tennis League, which has the mission to bring tennis, fitness and life’s lessons to inner-city, underprivileged boys and girls as well as handicapped and wounded warriors. Dinkins became a member of its Board of Directors.

Over the years, NJTL has established youth tennis centers nationwide and has been instrumental not only in bringing promising new players to tennis academies but also by encouraging others to hone their academic skills to go on to colleges and universities. Children are given scholarships or grants for tennis instruction; they’re given extra help to make them better students in the classroom, learning the importance of good study habits and achieving academic success. Through the USTA Foundation, working together with NJTL, children are able to earn scholarships to college.

“Can you tell me of a couple success stories?” I asked.

“Marc Clemente, originally from the Philippines, for one. He is a product of NJTL, having started as a 10-year-old at the Central Park clinics. He graduated from Columbia University, played some professional tennis touring in Southeast Asia, started a successful coaching career, part of which was at NJTL, and now he is in sports marketing having worked with the Tennis Channel, CBS and the Today Show, before going to The Singapore American School as Director of Marketing and of Tennis.

“Another fine product of NJTL is Katrina Adams, the president of the USTA, the first African-American and former professional tennis player to lead the USTA. Katrina grew up in Chicago and in 1975 joined a tennis clinic when she was 6. But, the next year she joined the NJTL program in Chicago and has remained involved ever since. For the past ten years, she has been the executive director of the Harlem Junior Tennis and Education Program, one of NJTL’s facilities. She went on to play at Northwestern, winning the NCAA’s doubles title and then joined the pro tour, having a world ranking as high as No. 67 in singles and No. 8 in doubles. She has been a commentator on Tennis Channel since 2003 and now leads the USTA.

“I’m very proud of NJTL achievements. And I’m hopeful too that these young people will stay in the game until they’re as old as I am,” concluded Dinkins, beaming with a smile.

Can you imagine playing doubles with the likes of Roger Federer, Rod Laver, John McEnroe, Monica Seles, Serena Williams, Ilona Kloss and Billie Jean King? Each week until Dinkins stopped playing at age 88, the Mayor’s secretary sent out email blasts to 64 of his best tennis playing friends, finding out who’s available for the matches that week. They’re on the list and play whenever they can.

“My son Davey is also on the list,” said Dinkins proudly. “He’s 60 now and has become a pretty good player!”

“Ilona Kloss was on my list. One day I picked her up and, to my surprise, Billie Jean was with her. Billie Jean was recuperating from an injury so didn’t play, but she wanted to watch our match. When we arrived at our usual court at Roosevelt Island where I always played with Billie Jean, the crowd went wild. She inspires not just the little girls but boys too and not just in tennis. In all areas of our daily lives, she inspires.”

Soon after Seles, then the world No. 1, was stabbed and injured on court during a tournament in Hamburg, Germany in 1993, Dinkins met her in Monte Carlo. She was playing in a Pro Am there and Dinkins was immediately impressed by her as she struggled to recover mentally and physically from the attack.

“I’d always been a fan of hers. Then after the stabbing happened, we became fast friends,” the Mayor explained.

She didn’t return to professional tennis for more than two years, but Monica played in Arthur Ashe Kids’ Day. Her partner? The Mayor. Their opponents? Mike Wallace of CBS “60 Minutes” fame and Martina Navratilova.

The Mayor said, “We were at match point, Mike was at net, and by some fluke he stuck his racquet out at just the right moment and hit a short volley that we couldn’t get. But that loss didn’t dampen the friendship between Monica and me. We’re still very close.”

“Plain and simple, it’s a fun sport! Of course the most fun is winning,” said the Mayor. “But millions simply become better people through tennis.”

“How’s that?” I asked.

“For one, you do yourself a favor and keep in shape. I was always a singles player, but later started playing doubles. When you reach your 80’s, doubles is better for you,” he added with a smile. “I stopped playing when I turned 88. But, I still love the game, love the people I’ve met and the thrill of watching top tennis.

“You meet great people who become life-long friends. Psychologically, you feel youthful and energetic. You think young. You learn to play by the rules because if you don’t, you get called on it. Players who cheat – word gets around and they’re not invited back. As I mentioned when playing with my Deputy Budget Director Norman Steisel, you learn about one’s character when playing tennis.

“I remember watching Ashe play Jimmy Connors one night at Madison Square Garden. At a crucial point a linesman called one of Connors’ shots out. Ashe corrected him saying, ‘No that ball was good’ giving the point to Connors. Ashe was such a fine ambassador of tennis and an example of what integrity is.”

He continued, “You tend to be more positive and optimistic, at least that’s been my experience. But, the best part is bringing this game to children. They become better kids and can be involved in the sport forever.”