by Randy Walker

@TennisPublisher

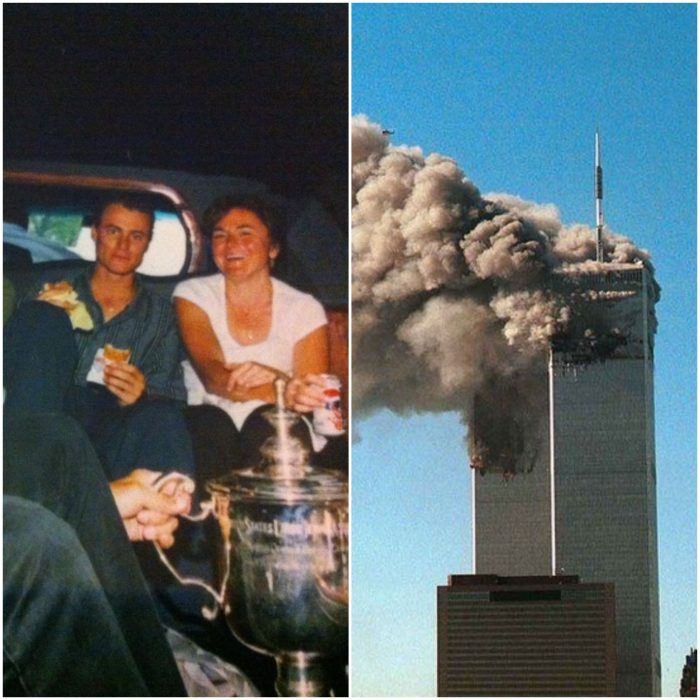

September 10, 2001 was a day of joy, satisfaction and reflection for Lleyton Hewitt.

The 20-year-old Australian was one day removed from decisively beating Pete Sampras 7-6 (4), 6-1, 6-1 to win his first major singles title at the U.S. Open in New York. Hewitt was the youngest man to win the U.S. Open singles title since Sampras himself won the title in 1990 at the age of 19. Photos of Hewitt in his bright red shirt and trademark backwards white ball cap graced the front pages of newspapers around bodegas and newsstands in New York and around the world. While Hewitt’s win was a major breakthrough, many of the stories focused on the perceived decline in the 30-year-old Sampras, who finished the Grand Slam season without capturing one of the big four titles for the first time since 1992. He seemed to run out of emotional and physical energy after back-to-back-to-back victories over Patrick Rafter in the fourth round, Andre Agassi in an epic quarterfinal, and defending champion Marat Safin in the semifinals in a match that avenged his loss to the Russian in the previous year’s U.S. Open final.

As was customary at the time, the U.S. Open winner would participate in a press tour the Monday after the tournament around New York City, the media capital of the world. As a member of the U.S. Tennis Association’s communications team I was part of Hewitt’s posse that traveled to various television shows to promote him as the newest young star of men’s tennis and the new U.S. Open champion.

We crisscrossed Manhattan in a stretch limousine with my lone responsibility being the safe-guarding of the U.S. Open men’s singles trophy, used for the photo opps and TV interviews. Lleyton was accompanied by his parents, Glynn and Cherilyn, his agent Kelly Wolf from Octagon and her assistant, as well as Miki Singh from the ATP and tennis writer Peter Bodo, who was writing a behind-the-scenes article on the media tour for Tennis Magazine.

I remember Lleyton had his huge smile on his face the entire day. When he was on the court competing, he seemed like such a rough and tumble hard core competitor, ripping groundstrokes with his hat on backwards, strutting around the courts like a mean swashbuckler. However, in this environment, he was very much like the 20-year old kid he was, not even able to legally drink. I can still see his rosy and freckled cheeks decorating his smile.

When the media obligations were over, we all went our separate ways and I returned home to Connecticut with the trophy. I hadn’t been home in about three weeks, holed up on site in the media room at the USTA National Tennis Center and at a hotel around the corner near LaGuardia Airport. I wanted to get home and, since I had the precious U.S. Open men’s singles trophy in my possession, I wanted to hold on to it a little longer and show it off some. I went to my mother’s house in New Canaan for dinner and gave her a chance to have a look at the trophy and take some photos. My roommates in the duplex I was renting at the time on Ute Place in Greenwich were also pretty excited to see the trophy up close before I had to return it the next morning to the USTA National Tennis Center in Flushing Meadows.

The following morning, September 11, 2001, I pulled out of the driveway and distinctly remember as I was backing up my Nissan Altima car out of the driveway hearing Charles McCord of the “Imus in the Morning” radio program report that a plane had struck the World Trade Center.

As I drove down I-95 towards the USTA National Tennis Center I continued to get updates on the terrible tragedy that was unfolding from Don Imus, McCord and famed New York City sports personality Warner Wolf, who called into the radio program to provide eyewitness reports from his apartment, just blocks from the World Trade Center.

As I approached the Whitestone Bridge, which separates the Bronx from Queens in Long Island, I anticipated that I would be able to see the smoking towers with my own eyes in the distance.

As I approached bridge, my mobile phone rang and I anticipated it was my mom or dad or a close friend. It was from a reporter from Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The USA vs. India Davis Cup matches where scheduled to be played there in 11 days and I was the press officer for the U.S. team. The reporter was perky and excited and fired off a flurry of quick questions about media scheduling and protocols.

I stuttered an almost incoherent response. The reporter fired off another enthusiastic question about how he could get a one-on-one interview with Andy Roddick or something. I was barely paying attention to the conversation as my mind raced about what was unfolding and as I approached the incline of the Whitestone Bridge where I imminently would see the World Trade Center with my own eyes. I glanced to my right and as the New York City skyline unfolded in my view, I could see the two towers burning in the distance. It looked as though the Twin Towers were like two cigarettes, with smoke coming out of the top.

“I’m sorry,” I said to the reporter on the phone. “I’m really distracted with everything that is going on. We are going to have to talk about this later.”

“What is going on?” asked the reporter.

“Two planes just hit the World Trade Center. It’s very likely a terrorist attack.”

I don’t remember that reporter’s name but his “9/11 Story” that he probably remembers each year is that he first heard the news of the attack from me.

“I’m driving over the Whitestone Bridge right now and I am looking at the World Trade Center on fire,” I said.

I quickly disengaged with the reporter as the New York skyline disappeared from view on my decline down the other side of the bridge. I pulled into the USTA National Tennis Center and brought the men’s trophy, blanketed in the distinguishable baby blue velvety Tiffany covering. I left the trophy with the assistant to Jay Snyder, the U.S. Open tournament director. There weren’t too many people on site and in the offices at the time, but those who were had their eyes glued to the television watching reports from lower Manhattan.

It was numbing to watch the buildings on fire and I felt a bit of a daze of sorrow and shock as I, along with the rest of the world, tried to make sense of the new reality that faced us. Another new reality suddenly dawned on me and that was that New York City may close all the bridges in the surrounding areas. If I don’t make it back over the Whitestone Bridge quickly, I may be stuck in Long Island for a while.

I left the U.S. Open grounds in haste and I could hear a flurry of police and fire sirens in the distance as New York’s bravest civil servants rushed to the scene. I drove as fast as I could to the Whitestone Bridge and remember in particular pushing hard on the gas as I swiftly traversed the Whitestone Bridge going north. I took a few glances over my left shoulder to again look at the burning Twin Towers. It would be the last time I would ever gaze upon them. Just after passing through the toll plaza, Warner Wolf described on the radio the awful scenes as both towers crashed to the ground one after the other. Phone calls from friends started to come in to make sure I was alright. I called my mother to find out if any of our friends or their children or relatives were at the World Trade Center. I tried to call my father in Alexandria, Virginia, but the call would not go through. I was fortunate that I did not know anyone personally who died on that day of infamy, but thousands did.

Hewitt had flown out of New York for Australia the previous night and he was informed of the attack by a flight attendant upon arrival in Sydney.