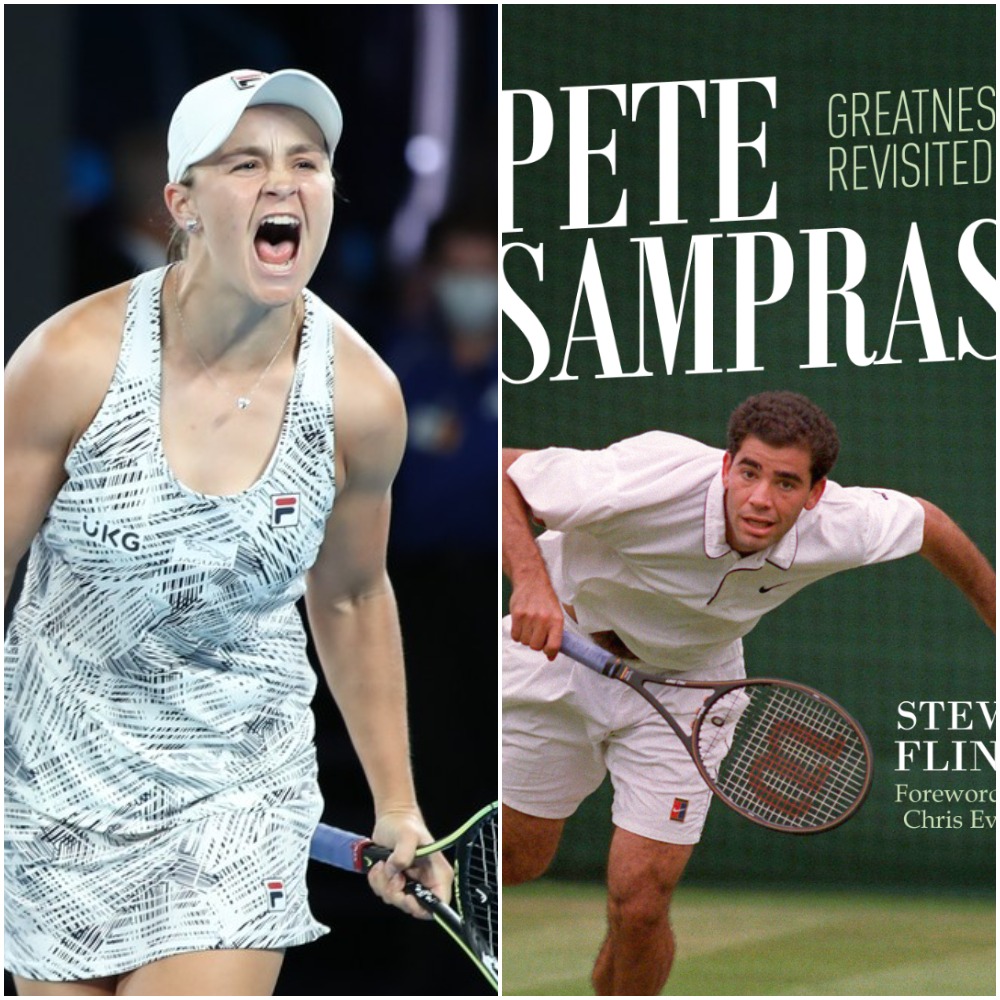

The sudden and somewhat surprising retirement of world No. 1 Ash Barty just weeks after winning the 2022 Australian Open brought up comparisons to Pete Sampras.

Like Sampras, Barty did a “walk off” ending to her career, announcing her retirement after winning her home slam at the Australian Open. Sampras, although not in the prime of his career like Barty, retired after winning his home Grand Slam tournament at the U.S. Open at age 31.

Steve Flink, the Hall of Fame journalist and author, wrote perhaps the definitive book on Sampras and his 14 major singles championships in his book “Pete Sampras: Greatness Revisited” (for sale and download here: https://www.amazon.com/dp/1937559947/ref=cm_sw_r_tw_dp_2RC7QZSHJ6XAKR741XJ8?_encoding=UTF8&psc=1)

In the end of the book, after Sampras won his 14th and final major championship at the2002 U.S. Open, Flink writes about the Sampras mindset following his emotional victory that eventually led him to decide to retire from the sport. An excerpt can be read below

The way Ivan Lendl looked at it, Sampras fit into a familiar pattern among champions who look for that last window of opportunity, and find it. He said, “If you look at the history of our game, most No. 1’s get one opportunity somewhere down the road when they are not expecting to do that much anymore and they grab it. They know how to win. It is like riding a bike. That was Pete’s opportunity and he took it.”

(Michael) Chang virtually echoed Lendl in his assessment. He said, “The motivation for Pete at that last U.S. Open was very evident. He went through the draw and had his opening and opportunities and he knew. It was like, ‘This is my chance.’ And he took advantage of it. If the opportunity presented itself he would be there and take advantage of it as only Pete can.”

In an interview for this book, Rod Laver said, “Pete always had that championship nature. Winning that U.S. Open at the end was a great tribute to him. Most top players don’t stop that way, leaving the game on top. He did it. Pete was just a great champion who knew how to win under pressure.”

Annacone treasured the memory of Sampras’s triumph over Agassi as he spoke about it in 2018. He said, “I will never forget sitting courtside and watching the big screen with Andre and Pete standing in the hallway before their final. To this day I have never had a feeling like that in tennis. The hair on my arms and legs was totally standing and it was just total goosebumps. I thought the building was going to collapse when they flashed to those two guys in the hallway. This is where it had all started 12 years earlier with the same two guys in the final. I remember Pete saying the night before their ‘02 final, ‘This is awesome. This is exactly where I need to be. I get to play Andre.’ He totally embraced the rivalry.”

Making it all the more remarkable in retrospect is the fact that Sampras was indeed wrapping up his career right then and there. Beating Andre Agassi in the final of the U.S. Open was his last official tennis match. How could anyone leave the sport under more extraordinary circumstances? How many athletes could turn that kind of dream into reality?

Annacone said, “I couldn’t believe that he was able to win this match and then never play again. This is the most amazing thing to me of all, the most incredible thing in sports that I have ever seen.”

Sampras remembered the feeling afterward his singularly satisfying 2002 U.S. Open triumph. He said in 2019, “I had to figure out what was next with my tennis. I didn’t know what to feel. I flew home the night I won the Open and just enjoyed that. Two or three months later I was talking to Paul about what was next and getting ready for Australia, but I was not emotionally ready. So I felt I would see how I felt about playing Indian Wells or Miami in 2003. I was still hitting balls but just didn’t want to do the work it took for the reward at the end. It just seemed unbalanced to me. I didn’t feel like doing the practice or the gym work. Something just came out of me that I can’t really explain. The moment when I knew I was going to retire was when I was in Palm Desert watching Lleyton Hewitt play a first-round match at Wimbledon in 2003, thinking that was the last place I wanted to be. That was when I knew I was done.”

Annacone recalled it slightly differently. He said, “We literally went six months of hitting a couple of days and then not hitting, getting ready for a tournament he did not end up playing. We had so many great talks about life. And then in April, when we were getting ready for Wimbledon, I walked in the front door when I came by and he said, ‘I am done.’ I said, ‘Done with what?’ And he said, ‘I am not playing anymore. I am done.’ He explained that he had done everything he wanted to do. He said he realized why he played and that was to prove to himself what he could do. He said he didn’t need to prove anything anymore.”

At the U.S. Open of 2003, an official retirement ceremony took place. Sampras had a lot of family there, including his parents. His wife and infant son, Christian, were out in the evening air on Arthur Ashe Stadium, sharing the celebration with him. No farewell could have been more fitting. Sampras had essentially announced himself to the tennis world at 19 when he became the youngest man ever to win the U.S. Open in the springtime of his career. Twelve years later, in the autumn of his career, with so many skeptics writing his professional obituary, when most of the tennis community at large was highly skeptical, he had closed the curtain with another triumph at the Open.

Reflecting on his sterling career now almost two decades after it ended, Sampras mused, “I could sit here now and look back on it and say, ‘Should I have tried a different and larger racket for the French Open? Sure. Do I wish I had communicated better about my health and that I didn’t have an ulcer for two years? Yes. I really do regret not communicating better with Paul Annacone and my team and whoever was close to me about what was going on.”

Having said that, Sampras believed, “There are always some regrets. Internalizing a lot of stuff contributed to my ulcer. I do remember one conversation with Paul Annacone in 1998 when I was trying to break the No. 1 record and I told him I was stressed out and struggling. My hair was falling out. I let my guard down, which was unusual. But I have very few regrets. I look more at the positives. I achieved some amazing things. I didn’t want to show any vulnerability. I didn’t worry about what people were thinking. Being self-willed and self-focused with the blinders on made me a great player. I kept things close to my vest.”

Following up on that theme, Sampras said, “You look at Roger and Rafa and Novak today and they are much more social and more outgoing than I was and maybe it is through social media and where we are in society. Maybe if I had been playing now I would have been more like these guys. It is just a different mentality. In my generation everyone was a little more separate and we all got along fine, but now Roger has Rafa’s text number and they all text each other and have Instagram. Knowing Roger a little bit, I guess he can be the life of the party in the locker room. I was more in the corner away from everyone and I loved it on the last weekend of Wimbledon when nobody was in the locker room. I am a lone wolf. I get energy being by myself. I like being alone. That is how I am wired and how I have always been and it was the way I liked it throughout my career.”

Speaking of how he viewed his illustrious career, what meant the most to Sampras was his longevity. “Being the best in the game for almost half of my career meant a lot to me,” he said. “I did it in a certain way that was humble and it was my style. I feel I was a talented player with a big game that made guys uncomfortable. I just tried to conduct myself the way I am, in a very understated way, keeping my emotions in check and being a good role model for kids on behavior. That was important to me and at the same time that is who I am. I let my racket do the talking and played big matches well and I felt that the bigger the match was, the better I am.”

He had established himself as arguably the best player in the history of the game with his unimaginable six years in a row at No. 1 and extraordinary 14-4 record in Grand Slam finals. He had gone out on a high note.

As Monica Seles said in summation, “It was a storybook ending to a great career. 329 Steve Flink Walking away is very hard for an athlete. You always ask yourself that question—when is it time to go? And for him that was as perfect an ending as you could write, winning the Open in his home country and [eventually] saying I am closing this chapter of my life.”