By Randy Walker

@TennisPublisher

Gianni Clerici is not the most famous inductee into the International Tennis Hall of Fame, but he might be the funniest. He was inducted into the class of 2006 in Newport, Rhode Island and I can still see him standing next to fellow inductee Patrick Rafter as the Italian national anthem was played and Gianni was singing and Rafter was laughing at the mischievous activities and mannerisms of Clerici.

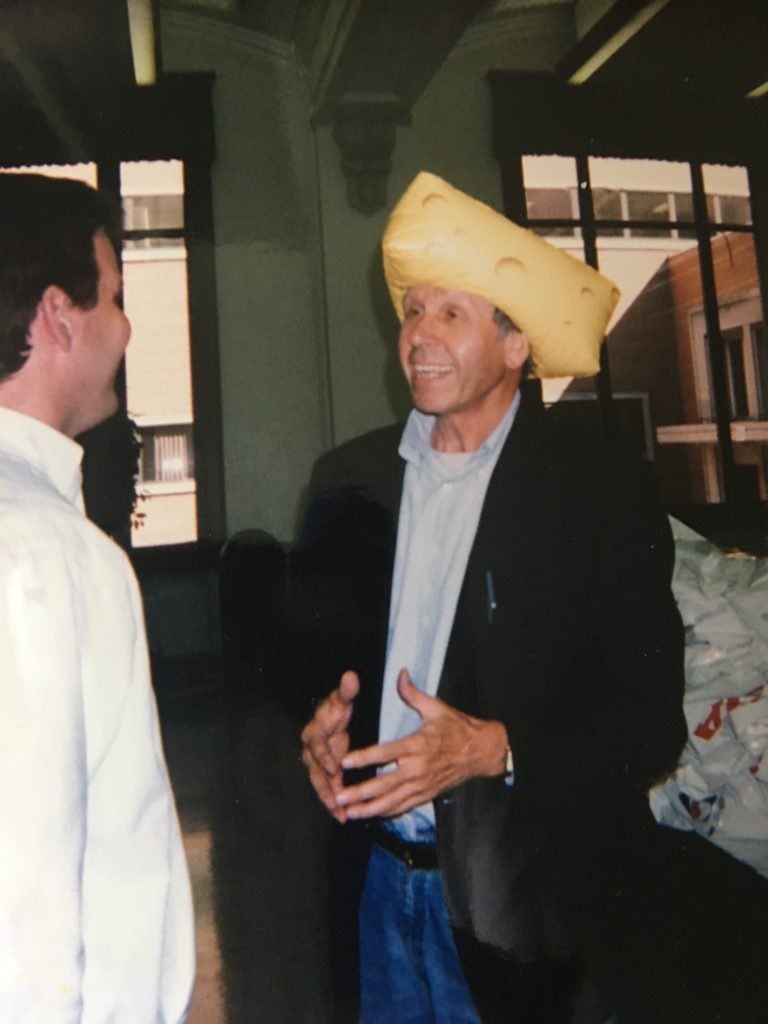

Clerici said “arrivederci” to this world on June 6 at age 91 and many tennis insiders are sharing fun stories about this charismatic man from Como, Italy. I have many memories of laughs and cheeky conversations with him in the press room at the U.S. Open and at Davis Cup. I was happy to quickly find in my stack of old photos a picture of him wearing an inflatable “Cheesehead” at the 1998 USA vs. Italy Davis Cup semifinal in Milwaukee, Wisconsin that we gave out in a media gift bag. I vaguely remember that I had to explain to him what a Cheeshead actually was!

Clerici is best known for his television commentary in Italy alongside fellow Italian tennis journalism icon Rino Tommasi. They were known mostly as a bawdy TV duo and their “off topic banter.” In 2002, Sports Illustrated featured the pair in a feature story, describing how, when bored commentating a match at the French Open between Juan Carlos Ferrero and Gaston Gaudio, that they spent a long stretch of the match “discussing the state of their sex lives and trying to remember the lyrics to various European folk songs.” Said top Italian player Rita Grande to Sports Illustrated, “Even people who don’t like tennis will watch them to hear what outrageous things they’re saying and doing. They are so funny if you have a sense of humor and don’t get offended easily.”

When I think of Gianni, I think also of Bud Collins as they were great friends and playful comrades in reporting, documenting and broadcasting tennis from that “old school” tennis journalism fraternity. With that, I posted Bud’s biography of Gianni as seen in Bud’s book “The Bud Collins History of Tennis” here below.

Hall of Fame—2006—Journalist

As an Italian boy of nine, summering in Alassio, beside the Mediterranean, Giovanni Clerici—the renaissance man from the renaissance land—was fascinated by tennis at a small local club, and learned the game on those courts of crimson clay. Fascination evolved to passionate love as he dreamed of a place called Wimbledon and imagined himself playing there as well as in Paris and Rome, and throughout Europe.

It happened. Seventy years have passed since his seduction by this game, and yet he continues to pursue it across the planet as a journalist of rare understanding and literary flair, a broadcaster of discerning, witty voice. Readers of Italian newspapers since 1951 (La Repubblica of Rome over the last two decades) have delighted in his reports as have televiewers for more than 30 years.

Giovanni Emilio Clerici was born July 24, 1930, at Como, and has lived there since. His seven journalistic predecessors in the Hall (four Americans, three English) wrote or broadcast in the English language. Clerici, the lively European newcomer, is the first to diversify, writing in his native Italian as well as French and English, broadcasting in Italian and French.

His writing has ranged far beyond newspapers, magazines— and tennis. A scholar of tennis history, he has delved into the game’s origins as deeply as the 14th century. From his meticulous research came the masterwork “500 Years of Tennis,” (4th edition, 2006), blending cultural moves with the sport from the Renaissance onward. He calls this massive tome “The Brick,” published in English, Italian, French, Spanish, German and Japanese.

Consumed by the history, he is ever willing to devote his expertise to projects such as the French tennis museum at Roland Garros, and the forthcoming Italian tennis museum at Milan. He is planning an institute to exhibit his magnificent collection of tennis paintings and sculpture, some of which have been displayed at Wimbledon.

Giovanni’s fresh approach to the game, often treating it humorously, has set him apart in his profession, and made itself felt in an extraordinary literary output. To his credit are two tennis instructional books, guiding many onto the court. A marvelous contribution brought to life the great, though mysterious, French star of the 1920s, Suzanne Lenglen, in his definitive biography, “Divina.” That led to a 2000 drama about Lenglen on the Roman stage.

No surprise to those who knew him as the honored author of Italy’s Best Play of 1987, “Ottaviano e Cleopatra.” His vast reach with intellect, pen and typing fingers has amounted to eight successful novels (two with tennis themes), four plays and a recent volume of poetry, “Posthumous in Life.” If he has departed from tennis from time to time, finding a variety of outlets for his unusual way with words, Giovanni has never strayed too far from his first love, and the addictive touch of putting racket to ball.

A youth falling for tennis in 1939, he was prevented by World War II from competing as a junior outside of Italy. That was a time of some danger for him, a teen-ager helping to smuggle guns to Italian partisans, guerillas harrassing the Nazis occupying Como. How could Giovanni have imagined then that he would become a player of international caliber and title-winning deeds, a trusted literary and vocal guardian of the game—and that the road from Alassio would lead across every continent to Newport?