Former U.S. Davis Cup standout Cliff Richey is continuing is crusade to raise awareness of mental issues, including depression in the adult male, with three upcoming appearances in support of his book ACING DEPRESSION: A TENNIS CHAMPION’S TOUGHEST MATCH. On May 2, Richey, the 1970 and 1972 US Open semifinalist, will speak at Millican University in Decatur, Illinois. He will also host a tennis clinic on May 1 at the Decatur Athletic Club where he will be co-hosting with Director of Tennis, Chuck Kuhle. On May 4, the Riverdale Mental Health Association of Riverdale, N.Y. will be honoring Richey and Ray Negron, a New York Yankees’ executive, for their contribution to mental health advocacy at a Gala dinner. The following day, on May 5, Richey will be the keynote speaker at the Mental Health Association of New York State Annual Spring Reception in Albany, N.Y.

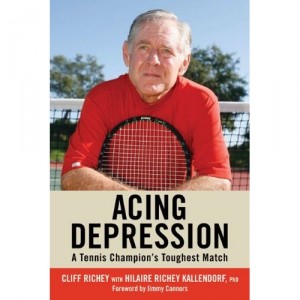

The following is an excerpt from ACING DEPRESSION: A TENNIS CHAMPION’S TOUGHEST MATCH ($19.95, New Chapter Press, www.CliffRicheyBook.com). In the book, Richey calls depression among adult males as “the silent tragedy in our culture today” and details his life-long battle with the disease that afflicts approximately 121 million people around the world. Co-written with his oldest daughter Hilaire Richey Kallendorf, is a first-hand account of the life and tennis career of Richey, providing readers with his real-life drama – on and off the tennis court. Richey’s depression is a constant theme, from his genetics and family history, to the tensions of his professional tennis career and family life, to his eventual diagnosis and steps to recover from his condition.

Depression is like a tennis match. There are some factors you can control, and others that you can’t. Depression is both genetic and acquired. I like to use the skin cancer analogy. You can be genetically predisposed to depression. It’s like having fair skin. But then additionally, through life circumstances or interests, you come under a lot of stress. That’s like being exposed to the sun. An investment banker with fair skin who works in a high-rise all day long probably won’t develop skin cancer. But a roofer (of whatever complexion) probably will. It’s a genetic predisposition. But anybody can develop it. It also has to do with nurture early on and life circumstances—whatever mix you happen to be dealt with all of those.

In tennis, you learn to limit the unpredictability of it all by concentrating on the factors you can control. I couldn’t control my leg muscles’ cramping. They would get so bad, so painful, that I literally would have a hard time walking. There were players who would use that as an excuse. I was never like that. Rather than use cramps as a cop-out, one of my incentives for training as hard as I did was to prevent them from happening. I used to run two or three miles a day in addition to tennis workouts. I did that for 25 years. The main thing I learned from Harry Hopman, the Aussie Davis Cup team captain, was that you need to be so fit physically that you can play as well in the fifth set as you did in the first. That, at least, is something you can control.

Likewise, you can show up early for a tournament to adjust to the climate, the altitude, and the court surface. One week you might play at high altitude. Then the very next tournament might be at sea level. In that case, you have to adapt in reverse. Everything feels slower and heavier. You feel like you’re running through water.

That’s what happened to me right after I won the South African Open. The next tournament after that was on clay in Charlotte, North Carolina. You tend to have longer points on clay anyway. You stay at the baseline longer. You play longer rallies. Also, in that climate, there was more heat and humidity. So I had several conditions conspiring against me that week. I lost to Ken Rosewall in the final.

The other factor that week, of course, was psychological. I was coming down off a really big win. There’s a certain manic high to that. Once again, there I was, flying pretty high. I was playing at high altitude, having a heady experience! After that it was time to go back to the U.S.—in essence, to come back down to earth. There are some specific psychological pitfalls to which athletes

are more prone. It’s dangerous to get too high after a good performance or too low after a bad one. Any good coach will tell you: “Stay away from extreme emotions. They are a trap.”

Unfortunately, the sports world promotes that “extreme” type of thinking. You would think that your self defenses or human instincts, some sort of internal guidance system, would steer you away from things that are particularly stressful. But it’s just the opposite. It’s like a magnet. Like how once you have been abused, you’re attracted to abusive people. At some deep, subconscious level, I had to know that putting myself right back into the crucible of competition was bad for my fragile mental health. But once you’ve tasted the drug of winning, it’s almost like gambling. Even when the odds of success are lower, you still want to try. It’s very, very hard to give that up.

Losses hit me even worse because of the negativity of depression. Dick Savitt, one of the old-time tennis greats, won Wimbledon in 1952, but shortly after that, he told Dad that he found his losses were starting to hurt him too badly. He found himself sitting in the stands