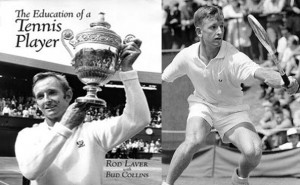

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Rod Laver winning his first of four Wimbledon titles. His 1962 and 1969 titles at the All England Lawn Tennis Club were the third legs of historic Grand Slams, the latter of which is chronicled in detail in Laver’s memoir THE EDUCATION OF A TENNIS PLAYER ($19.95, New Chapter Press, www.NewChapterMedia.com). The following is an excerpt from the Rocket’s memoir that discusses the magic of the grandest tournament in tennis. The book can ordered directly from Amazon.com here: http://www.amazon.com/dp/0942257626?tag=tennisgrancom-20&camp=14573&creative=327641&linkCode=as1&creativeASIN=0942257626&adid=1PMHX5TQXE64AFQMAZ5Q&

Wimbledon

That’s all you have to say. Everybody gets the idea. It’s not really the name of the tournament, although by this time it might as well be. Actually this world championship, regarded as the British championship, has been called the Lawn Tennis Championships since it began in 1877. It could be called The Tournament, and everybody would understand. The name Wimbledon comes from the London suburb where the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club has its grounds. They are magnificent grounds, big league by any standard, dominated by a stadium that is Centre Court. When Centre Court is full, which is always, 15,000 spectators are there, 3,000 of them standing sometimes six and seven hours, packed like a cattle car (although that cozy custom has been abolished).

“When they faints, they faints standing up,” an usher told me. “Somebody calls out to tell us there’s been a fainting, otherwise we’d never know, and somehow we push through and get the person.”

Nobody minds. You brought your lunch and entered the standing areas at noon. It stays light well into the evening in England, so that you might still be wedged into that fresh-air hole of Calcutta watching tennis at 9:15 p.m.

Faintings are not passed off casually at Wimbledon. Statistics are compiled and are announced every year by St. John Ambulance Brigade, the medical unit in attendance, and in 1969 the crowds obliged by setting an all-time Wimbledon fainting record. No fewer than 1,700 passed out during the twelve days.

A Grand Swoon, wouldn’t you say, old chap? St. John Ambulance gave that figure to the press as proudly as a football press agent trumpeting a scoring record. One customer out of every 190 was treated to St. John smelling salts. I have never keeled over at Wimbledon, but when I consider what a fashionable place it is to faint, and the efficiency of the care, I shall never fear when feeling queasy there.

Numerous changes have been made since I played there. A new Court 1 with 11,000 seats appeared in 1997. Copying the Australian Melbourne Park, Centre Court was fitted with a retractable roof in 2009 while the so-called “Graveyard” – intimate Court 2, burial ground of favorites – was rearranged. At the outside courts, it’s still a standing, jamming proposition with herds pressing against the fences that enclose the courts. During the first week when all the courts are in use, the crowds are over 30,000 daily, and surely they could sell 50,000 seats in Centre Court if they were available.

Considering the incredible success of Wimbledon, the men like Herman David, who ran the place, emerged as extremely principled blokes in their determination to stage an open Wimbledon in 1968 in opposition to the wishes of the International Lawn Tennis Federation. Wimbledon has always sold out regardless of the quality of the tennis. The British love it and the game so much they’d turn out to watch Ma and Pa Kettle play mixed doubles against the champions of Spearfish, South Dakota. But Wimbledon stood for the best, and insisted on being the best in more than name.

Wimbledon pressure has to do with the event itself. This is the world championship, a sports event that everybody pays attention to. For two weeks of the year Wimbledon is a big story on all the world’s sports pages, even in cities where tennis has little or no importance. There is no such thing at Wimbledon as an insignificant match because wherever you play, even on the most remote court, people will fill the spectator areas, whether there be grandstands or merely standing room.

The actor on Broadway, the singer at La Scala, the dancer at the Bolshoi Theatre understand what the tennis player at Wimbledon feels. So does the golfer at the Masters, the football player in the Super Bowl, and the baseball player in the World Series. It isn’t the money. The connoisseurs are here. We play for ourselves, and we perform and play because it’s in us and we must. We would do it whether or not anyone bothered to watch us. But we also play to be seen, to gain attention, to please and impress others. That’s an important part of it. My love for tennis goes to my depths, but when the time comes that I can’t play the Centre Court at Wimbledon, something vital will have gone out of that love.

The connoisseurs are the fans who pay to get in and the critics of the press, radio, and television who don’t. At Wimbledon, they’re the keenest in the world. We can feel the expertise of these people, even though they’re the quietest spectators and the least intrusive critics.