By Christopher Lancette

Five years may have passed since current world No. 81 Alex Bogomolov Jr., got the worst news of his pro career but the memory still burns inside him even at age 30 as he returns to the Citi Open in Washington D.C. this week.

With a cast on his left wrist due to recent ligament damage suffered at a tournament in Korea, the Russian-born American headed to Texas in 2008. He thought that all he needed was time to rest and recover so that he could resume a career filled with equal parts great promise and personal distraction. That’s when a doctor called him with a shot he didn’t see coming.

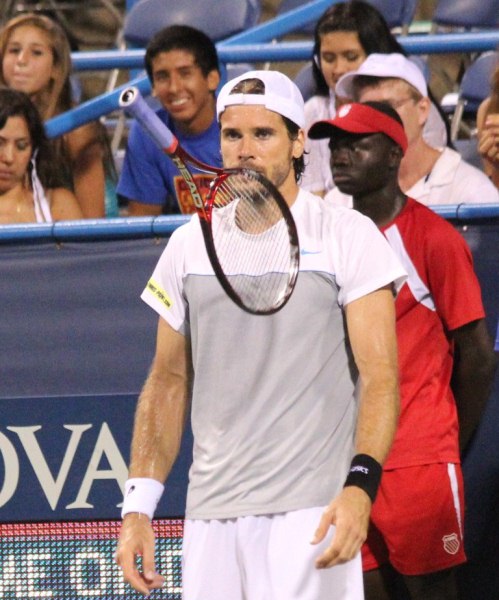

Alex Bogomolov, Jr. Alex Bogomolov, Jr. |

“He called me and told me I might be done,” Bogomolov recalls, his speech slowing as he relives the moment. “I remember sitting in a parking lot bawling.”

The then 25-year-old was in shock. A decade had passed since he burst onto the tennis scene by winning the USTA National Boys 16’ championships – beating Andy Roddick in the final – He won the Boys’ 18s and then began to learn how to win at the pro level, reaching the 130s in the rankings.

At the lowest point in his career, though, serendipity stepped in. It took the form of two people.

The first was Dr. A. Lee Osterman, a gifted hand surgeon that “Bogie” calls “the magician.” Osterman found a way to repair the pro’s wrist and give him a chance to fight his way back on to the court, even as his patient’s ranking fell from No. 167 to 313.

Bogomolov grows even more elated when he talks about the second person who entered his life that year. Back in his hometown of Miami, he couldn’t do much of anything but count the days until his wrist came free.

“I had the cast on and I was just hanging out with friends,” he recalls. “We went to a car show. That’s where I met my wife Luana. She was working as a Mazda sales rep. She didn’t know anything about tennis and had no idea who I was.”

Bogomolov found something in Luana that he had not found in his personal life before: Genuine happiness. The new couple soon had a son Maddox, a child that the proud papa calls the light of his life.

The settled-down stability was a far cry from his bachelor days – a time in his life that led to his first marriage to WTA player and Playboy model Ashley Harkleroad that ended quickly in 2006. He also made headlines through his friendship with hitting partner Anna Kournikova. Tennis, he admits, wasn’t always his top priority as a teenager or young adult. Bogomolov also makes no claim that he was a Boy Scout.

Alex Bogomolov, Jr. Alex Bogomolov, Jr. |

“I grew up in Miami, and parts of it are rough,” he says. “I started running with some wrong crowds.”

Tennis played a role even in his mischief: At age 15, he would get his first taste of the U.S. Open … but not through a first-round invitation or qualifying win.

“I used to go to New York a lot as a kid,” he says. “Me and about five friends used to sneak into the U.S. Open, getting into the locker room without passes. We stationed ourselves at different posts and waited for players to make their way to an entrance. We’d ask them if we could carry their bags and then scoot right in with them.”

He became the No. 1-ranked USTA 18’s player by the year 2000. The same year, he earned a wild card into the Major he had only snuck into before. He lost to David Nalbandian in the first round at the U.S. Open but found that his appearance had suddenly made the tennis world aware of his talent.

“All of these agents starting coming to me and talking to me,” he says.

Out went plans to play for Texas Christian University; in came the decision to turn pro.

“As far as making a living playing tennis, I hadn’t thought that much about it until then,” he says.

Bogomolov fought his way through the challenger circuit and paid his dues at ATP stops in the years ahead. Misfortune slammed him again in 2005 when he was suspended for 1.5 months for failing a doping test. The punishment came despite the fact that a tribunal determined he had no intention of trying to enhance his performance by using salbutamol – which Bogomolov admitted ingesting through an inhaler he used to treat exercise-induced asthma. The decision robbed the player of prize money and rankings points earned by reaching the main draw of the Australian Open in 2004.

He met with greater success down under the following year, winning his first Grand Slam tournament match in 2006 – beating ninth seed Fernando Gonzalez of Chile in five sets.

Every time Bogomolov appeared to be poised for another major ascent in his career, adversity found its way to him. The 2008 wrist injury, though, would not knock him out of the game. While many players at that age are beginning to accept the notion they’ve risen as far in the rankings as they’ll ever go, Bogomolov refused to surrender to Father Time. With a beautiful new bride and baby boy in the stands cheering him on, he qualified for one ATP main draw and reached the quarterfinals or better in seven challengers in 2010.

His climb back up the rankings accelerated in 2011 – catapulting him to a career-best No. 33. Along the way, he notched the biggest win of his career by beating then No. 5 Andy Murray in Miami and No. 10 Jo-Wilfried Tsonga in Cincinnati. The success and 27 wins that year earned him the ATP’s “Most Improved Player” award.

Bogomolov hit another bump in the road in 2012 when he made the unusual decision to play for his birth country rather than the U.S. in the Davis Cup. Though chided by some of his American friends on the tour, Bogomolov says that it felt right to make the switch. His dad, after all, had been a Soviet national coach and the current Russian team had lost players to other nations. Russia lost to Austria in their February contest, Bogomolov dropping both of his matches.

Alex Bogomolov, Jr. Alex Bogomolov, Jr. |

If history holds true for the now 30-year-old, the setback will be followed by another leap forward. He often says that he believes success visits some players at a later age and that everything in life happens for a reason.

Bogomolov makes it clear that tennis means more to him now that it did as a can’t-miss prospect. He’s no longer playing just for himself but for his family. There is also another group of kids that he doesn’t forget – the kids that gather outside the U.S. Open dreaming of meeting or perhaps becoming a pro … just like he and his friends used to do.

“It’s a very special time for me now,” he says. “Now these kids are living vicariously through me. They see that I can do this, that I can achieve my dream.”

Photos By Won-ok Kim

Bobby Reynolds

Bobby Reynolds Bobby Reynolds (Left) and Ethan Park

Bobby Reynolds (Left) and Ethan Park Bobby Reynolds

Bobby Reynolds

Mark Ein (left) & Bobby Reynolds

Mark Ein (left) & Bobby Reynolds Alexandr Dolgopolov – Photo by Wonok Kim

Alexandr Dolgopolov – Photo by Wonok Kim Mica Gelb – Photo by Wonok Kim

Mica Gelb – Photo by Wonok Kim Irina Falconi – Photo by Wonok Kim

Irina Falconi – Photo by Wonok Kim Magdalena Rybarikova (L) and Wayne Bryan – Photo by Wonok Kim

Magdalena Rybarikova (L) and Wayne Bryan – Photo by Wonok Kim Lindsay Lee Waters – Photo by Romana Cvitkovic

Lindsay Lee Waters – Photo by Romana Cvitkovic Alexandr Dolgopolov – Photo by Wonok Kim

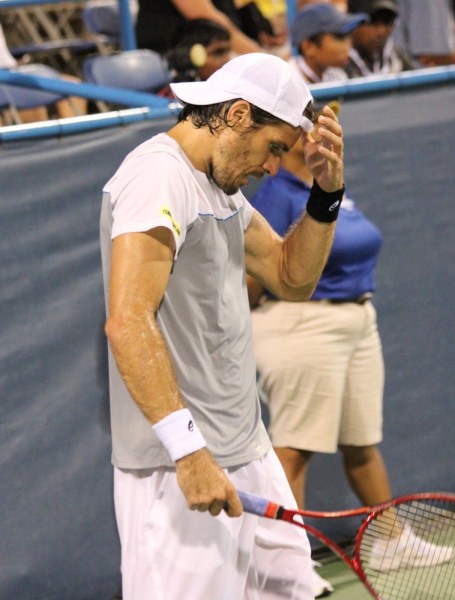

Alexandr Dolgopolov – Photo by Wonok Kim Tommy Haas – Photo by Wonok Kim

Tommy Haas – Photo by Wonok Kim

Magdalena Rybarikova – Photo by Wonok Kim

Magdalena Rybarikova – Photo by Wonok Kim Tommy Haas – Photo by Wonok Kim

Tommy Haas – Photo by Wonok Kim Mardy Fish (L) congratulates his close friend Tommy Haas after the match – Photo by Wonok Kim

Mardy Fish (L) congratulates his close friend Tommy Haas after the match – Photo by Wonok Kim Alexandr Dolgopolov – Photo by Wonok Kim

Alexandr Dolgopolov – Photo by Wonok Kim Alexandr Dolgopolov – Photo by Wonok Kim

Alexandr Dolgopolov – Photo by Wonok Kim Mardy Fish – Photo by Wonok Kim

Mardy Fish – Photo by Wonok Kim Sam Querrey – Photo by Wonok Kim

Sam Querrey – Photo by Wonok Kim Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova – Photo by Wonok Kim

Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova – Photo by Wonok Kim Magdalena Rybarikova – Photo by Wonok Kim

Magdalena Rybarikova – Photo by Wonok Kim Lindsay Lee-Waters – Photo by Romana Cvitkovic

Lindsay Lee-Waters – Photo by Romana Cvitkovic Lindsay Lee-Waters (Left) and Christopher Lancette – Photo by Won-ok Kim.

Lindsay Lee-Waters (Left) and Christopher Lancette – Photo by Won-ok Kim. Darrel Green

Darrel Green Rocky McIntosh (left)

Rocky McIntosh (left) Rocky McIntosh (center) and Mark Ein (left)

Rocky McIntosh (center) and Mark Ein (left) Arina Radionova (left) and Bobby Reynolds (right)

Arina Radionova (left) and Bobby Reynolds (right) WTT 2011 Championship Ring on Murphy Jensen’s finger

WTT 2011 Championship Ring on Murphy Jensen’s finger Michelle Obama (left), Sasha and Malia (right)

Michelle Obama (left), Sasha and Malia (right) Martina Hingis

Martina Hingis Darrell Green and Leander Paes (Left); Murphy Jensen and Bobby Reynolds (Right)

Darrell Green and Leander Paes (Left); Murphy Jensen and Bobby Reynolds (Right) Leander Paes (Front) and Bobby Reynolds, The Washington Kastles -Photos by Won-ok Kim

Leander Paes (Front) and Bobby Reynolds, The Washington Kastles -Photos by Won-ok Kim Radek Stepanek (Left) and Leander Paes -Photos by Won-ok Kim

Radek Stepanek (Left) and Leander Paes -Photos by Won-ok Kim Madison Keys

Madison Keys Bobby Reynolds

Bobby Reynolds