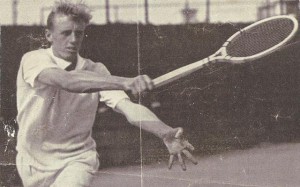

One-hundred years ago today, Nov. 1, 1911, Sidney B. Wood, one of the most charismatic and interesting characters the world of tennis ever had, was born in Black Rock, Connecticut. Wood’s life, which included a Wimbledon singles title, relationships with some of the most beautiful and famous women in the world, and many entrepreneurial pursuits, is documented in his posthumously published memoir called THE WIMBLEDON FINAL THAT NEVER WAS ($19.95, New Chapter Press, available on sale here: http://goo.gl/PXc1N)

Those who have read this book have called it and easy and fascinating read. Ann Loprinzi of the Trenton Times called it “a surprisingly entertaining and wonderful read.” Chris Gorringe, the former Chairman of Wimbledon, called it “a great read.”

Wood’s introduction to the book is excerpted here…

Who Am I?

People tend to remember my tennis name (if at all!), not as one of the top three or four American players of my time, but for the uniqueness of being Wimbledon’s only winner by default. Even so, I was its youngest men’s singles champion at the age of 19 for over 50 years and its youngest male competitor at the age of only 15.

I had never given much thought to remedying this impression until I started digging up a bunch of old records that Tennis magazine had requested for a story. I had retained draw sheets of most major tournaments from time immemorial, and when I fished out those of our U.S. Nationals, now the US Open, and saw myself seeded four years at No. 3, twice at No. 4, and once each at No. 5 and No. 6, over an eight-year span. I literally wondered for a moment whether some kind of crazy misprint had occurred. When I then got curious about my international record against the world’s top 10, I was again startled and admittedly aglow at finding my one-on-one

numbers were a lot more favorable than I’d realized. The only discovery that might top this would be something like a missing birth certificate materializing with a decade-later-than presumed nativity date.

In our day, to be chosen as one of your country’s two Davis Cup singles players was every player’s ultimate hope. As a married, depression-years’ breadwinner from the time I was 21, paying the rent came before putting trophies on the shelf. Most all of my top-ranked U.S. opponents were holding down tennis-related jobs, permitting practice and tournament play for a good part of the year, but even as a full-time working stiff (though my own boss since 22), I did manage to steal away four times to Wimbledon or on Davis Cup team junkets, but never got within half a globe of Australia.

Most years, I would head east for our late August National Championships from my California gold and sulfur diggings, barely ahead of the first day of the tournament, figuring to adjust to the grass during the first round or two. But let me tell you, more than once I got bounced before I knew where I was. The clanking, metal-body 14-passenger Ford tri-motor planes, replete with sick bags, and ammonia capsules, rarely made it in even twice the 29 hours advertised, usually with risky Rocky-Mountain weather sleepovers on wooden benches at tiny airports. No alibis, only reciting one of the reasons I thought of myself as an underdog against my more frequently competing peers — though I now may just consider re-writing my epitaph! Striving to maintain whatever tennis eminence one managed to attain in those no-pay-for-play years can’t sound too glamorous, but I wouldn’t trade a single season’s memory for whatever goes for achievement and camaraderie today.