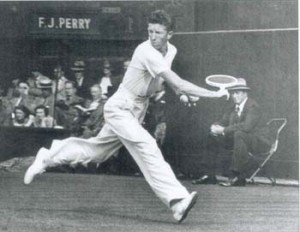

Don Budge, who was born 96 years ago on Monday, June 13, is called the greatest player of all time in the new book by Hall of Famer and 1931 Wimbledon champion Sidney Wood called THE WIMBLEDON FINAL THAT NEVER WAS. “A no-brainer,” wrote Wood when listing his top 15 players ever. “In 1938, Don was the first winner of the Grand Slam and for six decades he has been recognized by his peers as the one player to have commanded not only every shot in the book for every surface, but also to have been blessed with the single most destructive tennis weapon ever—a bludgeon backhand struck with a sixteen ounce “Paul Bunyan” bat.”

THE WIMBLEDON FINAL THAT NEVER WAS ($15.95, New Chapter Press, www.NewChapterMedia.com) details the life and times of Wood with a focus on one of the most unusual episodes ever in sport when he won the men’s singles title at Wimbledon by forfeit. Wood, who not only played tennis with Budge but opened a laundry business with him, has an entire chapter of THE WIMBLEDON FINAL THAT NEVER WAS dedicated to Budge, excerpted below.

Chapter 16 – J. Donald Budge

This cramoisie-cropped grand slammer made his contemporaries feel like welterweights going against a heavyweight. Don’s trenchant serve was a major weapon, but probably the single most ravaging stroke the game had seen was his prodigious backhand. Clubbed with a 16-1/2 ounce, Paul Bunyan bat (just try wielding one sometime), the basically flat-hit shot would sear the turf and devastate defenses.

You had to overplay a lot of returns to stay with the great Budge. When Don was serving, whether he came up or stayed way back, most of us felt we had to go for broke on most returns or be buried by the weight of his next hit. This meant taking just too many chances, and though you can get lucky for an occasional service break, the percentages always caught up.

Except for a very few exceptional second-servers of the era such as Ellsworth Vines, Gottfried von Cramm, Jack Kramer and Pancho Gonzales, serve and volley tactics against Budge were strictly Russian roulette. You would hear even Jack Kramer, the original serve-volley master, say that while Budge, fellow American Frank Kovacs and Australian John Bromwich were three guys he wouldn’t go in against consistently, Don was by far the roughest of the three. Against almost anyone, the serve-volley player, which most of us were in my generation, figures to have an 80 percent chance of holding service, particularly on grass. Even from love-40, you would expect to win a good percentage of service games.

But against Don, it was another ballgame. If you didn’t get your first one in, it left you two evil choices: go in and pray you wouldn’t get stripped, or stay back and prepare to scramble. From most receivers, you can force a chipped or high backhand, and a reasonably deep first volley lets you close in or force a juicy lob. With Budge, you had to almost always go for the low odds, an extra hard punch or be blunderbussed by his return.

I played every big player around for almost a quarter of a century, from the time I was fifteen, and even long past my serious tennis days, and I have felt reasonably in control of things when I served, and well in the match when receiving. But on my best days, Don – and only Don – could make me, and all but one or two others, feel he was a clear rung above us on the ladder. There was a side to Budge other than that seen by spectators when he was in all his majesty. Don was someone who’d rather relax than work, but was always ready to work at fun and games. He was witty, entertaining and, on occasions, downright playful. All in all, a nicer fellow to have around than play against.

To go back a way, I first noticed Don at the Berkeley Tennis Club, where he was trailing after his big brother Lloyd like a Rhode Island Red baby chick, carrying a racquet that looked huge because he was so tiny. Both were red-thatched, and Lloyd, at 17, could have put his carbon copy brother of 11 in his pocket.

The next time I saw this baby chick he was all rooster. It was at New Jersey’s Orange Lawn Tennis Club where I had reluctantly agreed to give up a weekend to play the annual East-West matches. I was always pretty nice to the newcomers and particularly when they were from my early days’ club, as Don quite shyly reminded me that he was. I started off gently with him – too gently. Before I could realize that this crazy looking, skinny kid was actually a backhand disguised as a man, it was too late to recover and he took me.

On Don’s first trip east from his Oakland home, he was 18 and his game showed the potential it was later to realize. In that year’s U.S. Nationals, he looked like such a sure comer that I went right to the USA’s Davis Cup Committee and told them they couldn’t leave him off the next year’s squad. I told them that with another year of seasoning, beginning with Wimbledon in June, he would be a shoo-in for one of the singles berths the following year. Had I only known how fast Don was to mature, I might not have been so insistent – for Don took my place as one of the two singles players that same first season. Of course, Don went on to achieve many glories on the tennis court, becoming the first player to win the Grand Slam in 1938, sweeping all four major singles titles.