Who are the bad boys in tennis? There isn’t much to choose from in today’s crop of ATP World Tour, but back in the 1970s, the tour was stacked with ‘em. Ilie Nastase, John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors are the three most notorious “bad boys,” but one seldom discussed is former U.S. No. 1 and U.S. Davis Cupper Cliff Richey. In his new book “ACING DEPRESSION: A TENNIS CHAMPION’S TOUGHEST MATCH” ($19.95, New Chapter Press, www.CliffRicheyBook.com), Richey discussed the bad boys of tennis, in this exclusive book excerpt.

The most notorious Bad Boy of us all was without question Ilie Nastase. His nickname was “Nasty” because of the dirty tricks he pulled. I remember one match where he wore a T-shirt under his regular collared shirt and when he got mad at the crowd, he lifted up the first shirt to reveal his T-shirt with a picture of the infamous middle finger. He was literally saying “F you” to the crowd! I really think Nastase enjoyed the carnival atmosphere more than anything else. I think that was his way of escaping the pressure. He would take a situation and make it into something he felt more comfortable with. That way he could pretend he was in control. He won the French Open and the U.S. Open that way. He was known as the Clown Prince of Tennis.

Nastase is still a good friend of mine, but there was a time when we didn’t speak to each other for a full year. During one match we played, the base linesman called a foot fault on his serve. Nasty kicked his shoe off at the linesman. I was waiting for him. He pretended that he couldn’t untie the knot to get his shoe back on. I finally said to the umpire, a guy named Hague Twofink, “I’m not putting up with this. The rule says ‘continuous play.’ I’m claiming the match.” I took all my stuff and went back to the locker room. I already started talking to reporters about claiming the match. My host that week, Bernie Koteen, came to get me and said, “You’d better go out there. They’re about to default you.” So I went back out on the court and told Twofink, “I’ll play, but his foot fault stands. He only has one serve left. If he doesn’t put the ball in play within 10 seconds, I’m leaving. I don’t care who you give the match to.” Twofink agreed. He announced that Nastase would have 10 seconds to serve. Nastase refused. The crowd started counting down: “10, 9, 8,” etc. Nasty never put the serve in play and was defaulted.

One player who was emphatically not a Bad Boy was Arthur Ashe. In fact, he was the antithesis of all that. He was black, grew up in the late 1950s and early ’60s, and played tennis, which was at that time a white man’s game. His coach, a man named Walter Johnson, trained him to just sit back and take every bad call without saying a word about it. He told him not to be obtrusive, stick out like a sore thumb or become a “controversial” black man (whatever that is). Arthur always handled things really well. He was known as a gentleman on the court—and off the court too. But we all knew that if he had dared to rock the boat, he would have been destroyed by malicious racists who thought he didn’t belong there in the first place. As my roommate, Arthur was always intrigued by me because I made so many waves. I could get away with stuff that he would never have been able to.

For our era, the stuff we pulled must have seemed pretty bad, but our antics would have been more accepted in a different sport. Tennis isn’t like football or baseball. If you look at baseball—the classic American pastime—it’s a well-established tradition to complain about umpires’ calls. People would almost be disappointed if you didn’t! Those baseball guys, they scratch their crotch. They chew tobacco. They stream vulgarities. They’re covered with dirt. But tennis—now, that’s a different story. You’re supposed to sip tea with your opponent after it’s over. And don’t you dare complain about a line call! That’s not in the spirit of the game.

In fact, in baseball, hockey, and all the other big sports, there’s not a year that goes by that fights don’t break out between opponents—and occasionally even among teammates! In ice hockey, the saying goes, the fans came to see a fight—and oh, by the way, a hockey game broke out. In other sports, cursing is the standard. It’s actually considered a part of the fabric of athletics. So taking all that into consideration, I ask: what did I ever do that was so bad? I wouldn’t have been called a Bad Boy in any other sport. It was only because tennis was such an upper-crust game. When I first started, all the tennis players carried whitener with them in their bags. It was considered lack of decorum to walk out on the court if your tennis shoes were not perfectly white! I didn’t like all this prim and proper bullshit. We were actually almost timid compared to other sports. I was always proud of the fact that I brought a little more manliness to the game.

Was my Bad Boy image, at least in part, a creation of the media? It’s true, they loved to report all that crap. I was out there raising Cain, doing unusual things. I got unbelievable press coverage. I loved every minute of it. So in a sense you could say I courted the media, but I didn’t really do it for that reason. I never debased myself by cozying up to them. One time I got mad at a reporter from the New York Daily News, Mike Lupica, who credited my win over Laver in 1972 at the U.S. Open to Laver having a bad back. I started out the next news conference by saying, “Where is that reporter? I want to talk to him!” So I wasn’t out to make any friends, reporters included. I just got a lot of press coverage because of the way I was.

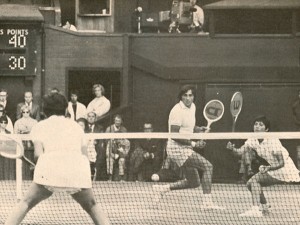

Looking back, it’s also probably indicative of how much the game has changed. The code of conduct was instituted for tennis after my era. (Who knows? Maybe they had to institute one because of me!) Once the code came in, they started taking points off for prohibited actions. Profanity was one. Guys like Connors and McEnroe would still utter profanities, but they would cover their mouths to muffle it so no one could understand the words. It was actually quite humorous the two times I played McEnroe, considering that I was almost over the hill at that point, while he was still a young kid. The first time was in September of 1977 at the Cow Palace in San Francisco. It was one set all, and he began to pull his shtick: going after the linesman, challenging the call, the whole usual tirade. Amused, I just sat back for a while and watched. Finally I got tired of waiting. My muscles were getting cold. I shouted, “John, for Pete’s sake, show some respect. You got nothing on me. I’m the Original Bad Boy! Let’s just get on with the match.” Suddenly he looked like a child who’d been chastened by an elder. He straightened up right away!

Three months later I played him again in the final of the Bahamas Open. Before the match I said, “Let’s make a deal. I won’t challenge the line calls if you won’t.” He agreed. We split the first two sets and got to 3-3 in the third. He got a call he didn’t like. He jumped the net, stormed over to my side of the court, and was about to start challenging the call. I cuffed him and said: “Get back over there. We had a deal.” Meekly, he put his tail between his legs and went right back over to his side of the court! Eventually I went on to win the match.

I love McEnroe. We see eye to eye on a lot of things. I may have beaten him on the court that day, but that didn’t keep us from being soul mates through the years. That match was like “Original Bad Boy meets Junior Bad Boy,” the tennis equivalent of “Madonna meets Britney Spears.”