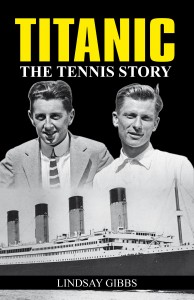

Just six weeks after incredibly surviving the sinking of the Titanic in 1912 – and nearly having his legs amputated due to surviving the night in the frigid waters of the North Atlantic – young upcoming American tennis star Dick Williams made one of the most unlikely – and perhaps the most spectacular – tournament debuts in American tennis history. Author Lindsay Gibbs narrates Williams plating in the Pennsylvania State Championships in her novel TITANIC: THE TENNIS STORY ($12.95, New Chapter Press, available here on Amazon.com: http://www.amazon.com/Titanic-Tennis-Story-Lindsay-Gibbs/dp/1937559041/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1354025193&sr=8-1&keywords=Titanic+Tennis+Story) The book tells the incredible stories of Williams and fellow tennis player and future U.S. Davis Cup teammate Karl Behr, who both survived the sinking of the Titanic, met on the rescue ship Carpathia and incredibly faced each other in the quarterfinals of the 1914 U.S. Championships (the modern-day US Open.) Gibbs narrates the incredible U.S. tournament debut for Williams in this excerpt below.

It had been almost ten years since Dick had been to Chestnut Hill, Pennsylvania to visit his uncle and namesake Richard Norris Williams. Chestnut Hill was a small, affluent town located just north of Philadelphia, named for the beautiful rolling hills it was built upon. It had originally been only farmland, but when the main line of the Pennsylvania Railroad was built, it became a popular place for prominent Philadelphia businessmen to settle and raise their families. It was quiet and while not as picturesque as Geneva, it had a similar charm about it.

Though the town was just as he remembered, his uncle’s home was far more ordinary than his eleven-year-old mind had pictured it. He recalled spacious rooms and lavish decorations. Now that he’d been around the world, these rooms felt adequate and the décor more rustic luxurious. Perhaps this was just the way things were after the tragedy: nothing in the world would ever seem quite as glorious and majestic as it had before.

His uncle had a car pick him up at the train station and a hot meal prepared when he arrived. They embraced when they first saw each other, but it was a rather forced hug, one that took place only because they each felt that the other was expecting it. The fact was, he and his uncle never had a relationship as adults. He had very hazy memories of Uncle Norris, remembering him being a bit quiet, uptight and bossy – the complete opposite of Charles – but it turned out that eleven years changed that perception too. Everything about his uncle now reminded him of his father – his posture, the way the lines on his face ended in distinct points instead of fading away, the way he paced in place when he was nervous (in sweeping loops around the room), the way he perked up his chest when he was preparing to talk and hit the beginning of his sentences with zest. These similarities made it hard to be around him and he sensed his uncle felt the same way. The two men never spoke of the disaster and spent most of their time in the house in separate rooms. It was the quiet Dick hoped for, but there was nothing comforting about it.

He didn’t want to sit around in silence all day. He wanted to play tennis. His hard work on the Carpathia had paid off. His legs were saved and he could walk normally. That, of course, was the important thing but Dick was anxious to get back on court, to see if he could do more than walk. He wanted to see if he could fulfill his father’s dreams. So as soon as he was settled in (and caught up on sleep), he walked the two miles to the Philadelphia Cricket Club and started practicing.

The first time he hit a ball he was so nervous that his heart was racing. He picked an outside court, far from spectators. The pristine grass courts had just opened for the season and were a hue of perfect green. Then, as he had done thousands of times before, usually under his father’s watchful eye, Dick Williams bent his knees, swung his racket around with his right hand in a perfect arc while simultaneously lifting the ball into the air with his left. He leaned forward, stretched as high as he could while keeping his left foot on the turf and struck the ball at the apex of its flight. The ball shot like an arrow to the intersection of service line and center line on the other side. It might have landed a few inches out, but that was the last thing Dick cared about. He had lost his father but he still had a gift from him: one of the best tennis serves on the planet.

Day after day he returned to the same outside court. His leg strength and movement rapidly improved and he had a better feel for the court than he’d ever had. When he was out practicing, the rest of the world faded away, his brain completely shut off. He just trusted his body and mind to work together in perfect unison. He would close his eyes and imagine the most fun and daring shot he could possibly hit and more often than not, he would find himself executing it to perfection. At last, he was completely in control.

On June 2, only six weeks after being told that his legs needed to be amputated, he competed in his very first tennis tournament in America: the Pennsylvania State Championships at the Philadelphia Cricket Club. He was a complete unknown to the other players in the field. In the locker room, he was surrounded by men who had many pages devoted to them in moleskin notebooks, now resting at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. Dick was a little bit star-struck to be in their presence. He kept to himself, quietly watching where the others put their gear in the locker room and where to go for practice and for meals. He wished that Karl were there to show him around, like they had talked about on the Carpathia.

To even get into the tournament, Dick had to play a preliminary round, against one W.H. Trotter, a man he knew nothing about but who looked to be pushing forty and quite comfortable with the prospect of playing an unknown kid from Switzerland in the first match. They contested their match on the sprawling lawn right in front of the clubhouse. Other matches were going on beside them and nobody was watching as Dick won 6-1, 6-1 in about thirty minutes. He also easily defeated his next three opponents: a Philadelphia millionaire named Craig Biddle, former intercollegiate doubles champ Allen Thayer, who he was happy to learn was not related to John and Jack, and the promising nineteen-year-old local boy William Tilden, Jr. Dick didn’t even drop a set.

He made it to the final where he was to meet Wallace F. Johnson in a best-of–five-set match. The winner would play the 1911 Pennsylvania State champion Percy Siverd in the Challenge Round for the title. Wallace Johnson was the 1909 intercollegiate singles and doubles champion from the University of Pennsylvania and a fixture in the top ten in the American Lawn Tennis rankings for years. Dick knew all about him – there were numerous moleskin pages devoted to him. This would be the biggest test of his rejuvenated legs. His body was beginning to ache as the consecutive matches began to take their toll. He was concerned about his stamina.

Before the match, he found a surprise guest waiting for him outside the locker room – Jack Thayer. As he walked toward his old friend, who stood there beaming from ear to ear, he found himself tensing up. Memories came rushing over him, memories he had been suppressing. He just wanted to focus on the match.

“What are you doing here?” he blurted out, hoping he didn’t sound angry.

“Dick, you’re all over the local papers. I can’t believe it. It’s just like your dad said. You’re going to be a star!” Jack said excitedly. Dick forced a smile, but he really just wanted to be alone in the locker room to prepare for his match.

“Well, thanks for coming.,” he said, wishing that he meant it.

“Of course. I’m glad you’re doing so well, Dick. It’s amazing.”

Jack’s voice sounded much more mature than Dick remembered. He took a good look at Jack, suddenly realizing how much older he looked and acted. There were dark circles underneath his eyes and no sparkle behind them like there used to be. Dick felt guilty.

“Are you okay?” he asked, though he was afraid of the answer.

“Yeah, I’m okay. It’s just been – well, you know…” Jack faded off.

“Yeah. I know.” He hoped he sounded sincere.

But he didn’t know. He had been so engrossed with tennis that the horror they’d been through felt like a lifetime ago. He knew that there were reasons to be sad, and he certainly hadn’t forgotten the loss of his father, but he was honoring his father by devoting himself to his sport.

A large crowd gathered for the final. Word around Philadelphia quickly spread about this kid from Geneva who was running through the tournament like wildfire. And Dick was having so much fun on the tennis court that for the first time in his life he didn’t mind playing in front of a crowd. In Switzerland, he always wished the people would go away and stop looking at him, but here he relished it.

He won the first two sets against Johnson with ease 6-0, 6-1, but in the third set he found fatigue catching up with him. He knew that if he lost the third set, he would be in for a fight and would be in trouble.

At 5-5 in the third set, with the crowd eager to see more tennis and urging on the well-known champion Johnson, Dick looked up and saw Jack in the crowd cheering him on. Suddenly he thought of the swim, the cold, the pain. He thought about the hours spent holding onto that lifeboat, the people who didn’t make it, the hours of walking and fighting he had been through on the Carpathia to get him to this moment. He fought through all of that. He made it through the unimaginable. He could win this tennis match.

He anticipated Johnson’s serve out wide and took the ball almost immediately after it bounced and drove it hard down the line, not giving Johnson a chance to react. This gave him a break point, and after getting a good return in play, he was able to come to net and connect with a high volley that was angled so far away from Johnson that he didn’t have a chance. Dick broke serve to go up 6-5.

The crowd rose to their feet with applause, so impressed by Dick’s level of play that they momentarily forgot that they had been rooting for Johnson to extend the match. They had never seen tennis played like this before – so carefree and aggressive. It seemed to come so easy to him. Dick smiled on court, soaked in the applause and let the adoration re-energize his legs. He tried to keep his mind focused. Looking across the net, he could already tell that his opponent was defeated. All he had to do was get a few solid serves in play to seal the victory. Johnson’s shoulders were slumped and his eyes were darting around, clearly distracted by the crowd’s excitement. Four points later, Dick hit his last un-returnable shot and walked to the net to shake Johnson’s hand. After this victory, he felt like he could do anything in tennis.

The next day, Dick went on to beat defending champion Siverd 6-1, 6-1, 6-1 to win the Pennsylvania State Championships. His body was exhausted, but the match didn’t last any longer than a practice set would have, so it didn’t matter. Siverd had nothing to challenge Dick’s game.

One tournament. One trophy. No sets lost. It was a debut unlike any tennis player had ever had on American soil.