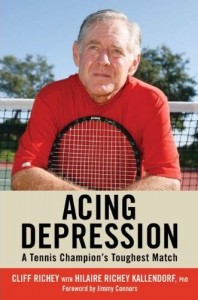

Depression is a topic that is in the news again with the recent suicides of Mary Kennedy, the wife for Robert Kennedy, Jr., and connected with NFL superstar Junior Seau. Cliff Richey, the former U.S. No. 1, Roland Garros and US Open semifinalist and star of the 1970 championship U.S. Davis Cup team, is the tennis world’s leading mental health advocate and the author of the book “Acing Depression: A Tennis Champion’s Toughest Match” which chronicles his triumph and continued battle with depression. In this exclusive book excerpt from the chapter called “It Ain’t All Autographs and Sunglasses,”Richey discusses depression in celebrities and sports stars and dealing with your life after the glory days are over. “Acing Depression” ($19.95, New Chapter Press, www.NewChapterMedia.com) is available wherever books are sold, Amazon.com and electronically and in hard copy here at this link to BarnesandNoble.com: http://www.barnesandnoble.com/

****

Clinical depression does not match the celebrity image. It’s so incongruous. And yet, the intersection of celebrity with depression is another argument in favor of its being recognized as a bona fide disease. It doesn’t just happen to the down-and-out. It can happen to anybody! Even to people who are hugely successful.

In fact, celebrities in general may be more prone to depression. There might be a correlation between driven, workaholic perfectionists and depressives. They are extreme people anyway. Depressed people who are highly accomplished may not feel or experience their successes in the same way as others. They never allow themselves to enjoy their victories. Not many people go into a profession with our same degree of vim and vigor. It’s no secret that within the celebrity world, we tend to call everyone else “civilians.”

In fact, celebrities in general may be more prone to depression. There might be a correlation between driven, workaholic perfectionists and depressives. They are extreme people anyway. Depressed people who are highly accomplished may not feel or experience their successes in the same way as others. They never allow themselves to enjoy their victories. Not many people go into a profession with our same degree of vim and vigor. It’s no secret that within the celebrity world, we tend to call everyone else “civilians.”

When Pete Sampras retired after winning more Grand Slam singles tournaments than any other man, he was quoted as saying, “Thank God I’m not on this merry-go-round any more.” There are a lot of guys who were great tennis players but had some of the worst personal lives you could imagine. Pancho Gonzalez was one of the all-time tennis greats, but he was often a miserable son-of-a bitch. He was married four different times. I remember once when John McEnroe quit a match. The umpire announced, “Mr. McEnroe has been forced to retire.” Then he turned off the mike and looked at McEnroe, who was sitting on his chair on the side of the court with his head down under his towel. The umpire asked, “Mr. McEnroe, may I ask what is the nature of your injury?” He replied, “Brain damage!” Of course he wasn’t serious, but that could be a metaphor for what the game did to all of us out there, sooner or later. It’s like a meat grinder. It just chews you up and spits you out.

If there is a pattern here, then why hasn’t it been talked about? Why isn’t this thing better recognized? One reason is that the “symptoms” or stresses of celebrity life probably mask the symptoms of depression. Celebrities already lead an abnormal life. Life on the tour itself was enough to create a monster, what with all the parties and free booze.

Another celebrity pitfall is to start believing your press clippings. To start thinking you’re invincible. I was good at tennis almost immediately. I was bringing home trophies already at age 12. In the juniors, I hardly knew what losses were. On top of that, you have people telling you that you’re special. Sporting goods companies are paying you to use their equipment. You’re making commercials. It’s all going your way. That’s one of the traps. You don’t want anything to come into your life that’s negative. When it does, it hits you doubly hard.

You’re used to being exempt. You don’t know how to cope with loss. When you put it all together, celebrity sports was the perfect little petri dish to grow the disease of clinical depression. I suspect a couple of tennis players I know are probably also prone to depression, but I’ve never talked to them about it. There was one other player of my generation who I think suffered from the same thing I have. I did a tennis outing with him after I went on an antidepressant in the late 1990s. We were talking about a mental health benefit golf tournament I had organized. Judging from his interest in Zoloft and my mental health activism, I felt like he had probably been on antidepressants himself, but he was afraid to come out with it. He is still making a living in the tennis world.

I don’t blame him. I know how it is. I don’t like the way it is, but I understand it. I don’t blame the poor guy. He still has to inhabit that world. I don’t. That’s one of the things that has allowed me to come forward about my illness: it doesn’t endanger my livelihood to do so. And it can potentially help lots of people. As a reporter for my local newspaper wrote, the decision to go public about my depression has constituted my biggest “ace.”

Maybe there should be a sub-genre of depression or a specialized diagnosis concerning a form of the illness that occurs only in celebrity athletes. That idea is not as off-the-wall as it may seem. They say there might be 18 or more different classifications within clinical depression. Some day we will know a hell of a lot more about it than we know now. It has been proven that mind-altering drugs such as heroin or marijuana can alter your brain chemistry. I wouldn’t be surprised if professional sports careers, with the high levels of cortisol and adrenaline involved, might provoke similar changes in your brain.

Some day depression may come to be recognized as part and parcel of the celebrity lifestyle. That lifestyle already fosters instability. You’re beholden to the public. You’re only as good as your last performance. Your whole life is lived in black and white. Guess what, guys? Celebrities are people too. We are not automatons. We still feel the pressure.

Celebrities are not robots, but sometimes we have to act as if we were. I remember back in 1969 in Las Vegas, we were in one of those old hotel casinos. We went to see a performance by comedian Alan King, who was a huge tennis fan. I said to him, “If I’ve had an argument with my wife, at least I feel like I can take it out on the tennis court. How do you go out there, if you’ve had a bad day, and still manage to be funny?” He said, “When you’re a professional, you have this little button that you push. You just go out there and do it. The show must go on.”

It takes a certain variety of person for me to really be friends with. My friends tend to be entertainers or athletes who have also led a lopsided life. Those guys who have faced that uncertainty every day of competition, that pressure of giving live performances on stage. We’ve been in that bunker together—in the trenches. I kid about being one of these guys who will die on the tour. We can’t find the exit ramp. You either have to be a little bit sick already to live on the tour—or else, sooner or later, it will make you that way!

I’m as particular now about my environment as I am about my friends. I really don’t like country club settings. I grew up in them as sort of an employee. I’ve met very few country clubbers who really knew what competition is all about. I know they’re the normal ones. I realize I am the odd one out. But I don’t even like resorts. That’s where I work. I don’t like the clientele that hang out there. I can’t relate to most of them. They aren’t my friends. It’s kind of an ass-backwards existence. But you get spoiled when you’re used to having all your trips paid for. I never go to sports events or resorts to be a spectator. I go to participate. I have to go by contract, whereas most people look forward to going there as the big event of their year. I’m more of a muni guy. I honestly prefer municipal golf courses.

I don’t like the sterile environment of resorts and country clubs. I’ve led a very exciting life. What an education! But at the same time, it’s difficult for me to enjoy what other people are dying to do. It’s like, if I were to just go on vacation, where would I go? What would I do? I guess I could do a little touring. See the Sistine Chapel and what not. But eating out, sightseeing, a football game, a concert— I don’t enjoy that stuff. I probably should want to do some of those things a little more. I know that I’m too set in my ways. But the exciting life I’ve led makes other stuff, frankly, start to seem a little dull.

The one thing I do value is success. I’m hung up on success the way a lot of people are hung up on being a member of a country club and having a lot of money. Success is my status symbol. Instead of being a jetsetter, I drive 25,000 miles a year. I enjoy it now because I never did that before. Most people work hard so they can afford to fly, not drive. I did exactly the reverse. I do enjoy going out to restaurants with friends or family some now. But after eating out every night on the tour for 30 years, it’s just not that big of a thrill. My substitute for eating out is going to a WalMart Supercenter to buy cold cuts, cole slaw and a loaf of bread. I take that and sack out in front of the TV at a hotel.

With the depression I’ve had, some people would go to a fancy spa to recover. I go to a municipal golf course. Either one can be a tool for seclusion.

I’ve thought about volunteering to clean urinals just to totally remove ego and see what that feels like. I’ve had a fleeting fantasy of showing up at McDonald’s and applying for a job. Perhaps volunteering with United Way for a year.

Maybe some day I’ll do one of those things. But even if I don’t, depression has been a humbling experience. I’ll never again be in danger of getting too impressed with myself. As the confluence of depression with celebrity demonstrates: it ain’t all autographs and sunglasses.