It was 100 years ago on August 13, 1914 that the Davis Cup Challenge Round between the United States and Australasia began in New York. The series is one of the most famous in the history of tennis for many reasons. It was staged as World War I raged in Europe for a second week. The venue was in the brand new West Side Tennis Club at Forest Hills, N.Y. – the future site of the U.S. Open for 62 years. Stands were erected to seat 13,000 fans – the most to ever watch a tennis match at the time. On the final day of play, American tennis fans became so involved in the match, they become the first-ever example of a “rowdy” crowd in Davis Cup competition – an attribute which now gives the competition its unique character.

The players for each team were also among the titans of sport at the time. For Australasia (a combined team of Australia and New Zealand), the team was led by Norman Brookes, the Australian who was fresh off winning his second Wimbledon title (not unlike Novak Djokovic of today). Brookes was so highly regarded at the time and in the future that the Australians named the men’s singles trophy for the Australian Open in his honor – The Norman Brookes Challenge Trophy. The teammate of Brookes was a Kiwi Anthony Wilding, one of the most dashing and charismatic tennis players ever – a man who rode his motorcycle across Europe – many times along train tracks – with his tennis racquets on his back going from city to city and tournament to tournament. Wilding just had his four-year run as Wimbledon champion ended by Brookes earlier in the summer and would unfortunately be the most high-profile casualty in World War I, being killed in action on May 9, 1915 at Neuve-Chapelle, France.

Leading the U.S. team was “the California Comet” Maurice McLoughlin, who was the two-time reigning U.S. singles champion and, along with Brookes and Wilding, regarded as being one of the top players in the world. Brookes, Wilding and McLoughlin were, you can say, the Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic of their era.

Add in as the second U.S. singles player, Dick Williams who incredibly survived the sinking of the Titanic two years earlier. Even more incredible than having one survivor of the Titanic tragedy be part of this series is having two, which was the case as American Karl Behr was also part of the U.S. team for the series.

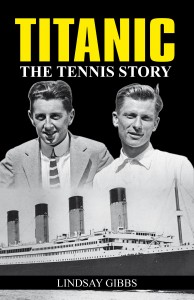

The story of Williams and Behr and their survival from the Titanic and subsequent triumphs in tennis, including being part of the same Davis Cup team and their subsequent meeting at the modern-day U.S. Open, are put into prose in the historical novel “Titanic: The Tennis Story” by Lindsay Gibbs.

The following is an excerpt / scene from the book TITANIC: THE TENNIS STORY by Lindsay Gibbs ($12,95, New Chapter Press, NewChapterMedia.com, available here:http://www.amazon.com/Titanic-Tennis-Story-Lindsay-Gibbs/dp/1937559041/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1348247347&sr=8-1&keywords=Titanic+Tennis+Story) that narrates this famous 1914 Davis Cup championship match at Forest Hills. Gibbs constructed the novel based on extensive historical research in newspapers, magazines and other periodicals and from historical first-person writings from the era and of survivors. She took creative license with dialogue and personalities and created certain situations in the novel, classified as a work of historical fiction

The summer of 1914 was full of tension. In late June, the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s murder set off a chain reaction of hostility in Europe between Austria-Hungary, Serbia, Russia, Germany and France that ignited a world war. When Britain became involved in the conflict on August 4, formally declaring war on Germany, it seemed improbable that the United States would be able to maintain its declaration of neutrality. As young men in Europe were thrown into battle, American men were still going about their daily lives, unsure if and when they might be called into action.

With one eye on the war, and despite his continued responsibilities at work and at home with Helen and their new baby, Karl, Jr., Karl Behr was managing to fulfill his promise to himself and was in the midst of one of the best tennis years of his life at the age of twenty-nine. He started out the season beating Alexander Pell and Gustave Touchard, two of the top players in the country, in the final and challenge round at the Middle States Championships to win his first title in six years. He was also feeling a lot of support from his peers as he successfully led a petition to get the U.S. Nationals moved from the coastal enclave of Newport, Rhode Island to a larger metropolitan venue at the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, New York, a move he felt was important for the future growth of the sport.

The popularity of tennis was at an all-time high – players from all across the country were traveling for months on end competing in tournaments. Fan attendance swelled, indicating the increased popularity of the sport. There were exponentially more tournaments in 1914 than when Karl was starting out. The U.S. Nationals were growing in prestige as more top players from overseas began to come over more frequently. Even within the United States, there were many more players from California and other parts of the country competing in events, further threatening the east coast domination of the sport. Universities were putting more emphasis and focus on tennis programs and Karl knew enough about business and fundraising to know that a small Rhode Island town could no longer keep up with the growing demands of the sport.

The 1914 U.S. Nationals was the final year the event was going to be staged at the Newport Casino. To top it all off, Karl had enough good wins over the summer to secure a spot on the U.S. Davis Cup team for the first time since 1907. This represented the achievement of an enormous goal for him; he had always wanted an opportunity to redeem himself for his country. And nothing made his father prouder than when he played on the Davis Cup team.

The United States was the defending Cup champion, thanks to the efforts of Dick, as well as Maurice McLoughlin in Britain the previous year, and therefore they would be hosting the Challenge Round. The West Side Tennis Club was selected as the site for the matches, to be played in early August, just prior to the U.S. Nationals. The Australasian team, led by four-time defending Wimbledon champion Tony Wilding of New Zealand and Australian legend Norman Brookes, emerged as the challengers to the United States.

Karl was realistic enough to know that he wouldn’t be picked for singles, as Dick and Mac clearly had those spots locked up, but he hoped he might get to play the doubles. He won quite a few doubles titles in his career, was the doubles runner-up at Wimbledon in 1907, and had the experience of beating Brookes and Wilding before in doubles. Now, playing the tennis of his life, he was hopeful for his chances. With his child being born and his father down to his final years, he wanted to seize any opportunity he had to make them proud.

But the Davis Cup, which promised to be the crowning moment in Karl’s career, turned into bitter disappointment. To begin with, it marked the first time since the Carpathia that he and Dick spent any significant amount of time together. They had great team camaraderie and experienced good times, but there was still an awkwardness the pervaded. They were not able to talk like they had on the Carpathia -– the team environment not conducive for long, one-on-one in-depth talks. Karl was also surprised at how uncomfortable he felt as the U.S. team clearly belonged to Dick and Mac. They won the trophy the year before in dominant fashion, were the best two players in the country for two straight years, and more than that, the two had formed a good friendship that made Karl feel even more like an outsider.

Karl seemed poised to be selected to play the doubles with McLoughlin as his consistency seemed to mix well with the brilliant but sometimes reckless shot-making abilities of “the California Comet.” McLoughlin was the reigning U.S. doubles champion with another Californian, Tom Bundy, but Bundy was not in top form and was not as fast on the court as in previous years.

Karl made a strong statement for selection to the team when he and a fellow American standout Ted Pell actually beat McLoughlin and Bundy 6-2, 6-3 in a practice match to help determine the team. “It would be a crime to leave Behr off the doubles team in the Davis Cup matches,” one top player even anonymously told the papers. But then Karl played a bad match — one bad match! — in the doubles semifinals of a tournament in Chicago, when he and Pell lost to a relatively unheralded team of G.M. Church and Dean Mathey from Princeton University and suddenly everyone was whispering that they’d better keep Mac with his old partner Bundy.

And that’s what happened. Karl was relegated to cheerleader status on the team. The U.S. Davis Cup Committee waited until the last minute to announce the doubles team, so late that Karl’s father, in his fragile health, went all the way out to Forest Hills only to watch his son sit on the bench.

For his part, Dick didn’t seem to be having a good week at Forest Hills. He seemed different to Karl. While he had transformed from a shy and inexperienced kid on the Carpathia into a confident and established tennis star, comfortable charming the crowds and being in the spotlight, he now seemed a bit more volatile. He put on a good show and continued to be as social as he had been, but it looked to Karl like the pressure was finally getting to him. It must be tough to win so much, Karl would think to himself sarcastically, unable to sympathize with the man who had so instantly jumped to heights of success that was not able to reach.

Karl would love to have had the pressure of playing Davis Cup matches, but against Australasia it seemed like Dick was out of sorts, seemingly unable to handle the hype, pressure and spectacle that the Davis Cup Challenge Round created. He would play a beautiful shot followed by some of the most silly and aggressive shots, and seemed to be walking around in a bit of a fog. He lacked consistency, making many errors and served with reckless abandon, hitting first and second serves with the same pace, causing many double faults.

Dick did not lose a singles match that counted in the entire Davis Cup competition in 1913, but against Australasia at Forest Hills, he lost to both Brookes and Wilding, unable to carry his weight and succumbing to the pressure and the fine play of his adversaries. In the opening match of the series, which was witnessed by a crowd of 13,000, the largest crowd to ever watch a tennis match, Dick was man-handled by Wilding 7-5, 6-2, 6-3. His four-set loss to Brookes on the third day of play clinched the Cup for the Australasians. Dick was not able to ascend to the heights of playing for his country as he did the previous year against the British team at Wimbledon.

As much as Karl was hoping for his country to retain the Cup, he couldn’t help but feel a modicum of vindication when McLoughlin and Bundy played one of the poorest exhibitions of Davis Cup doubles that reporters remembered, losing to Brookes and Wilding in three straight sets. That, combined with Dick’s lusterless performances, was what allowed the Cup to slip from the Americans grasp. And with war now raging in Europe – Brookes and Wilding set sail immediately after the matches for Britain to join their regiments as part of the British Commonwealth – one had to even wonder when there would next be a Davis Cup competition.

McLoughlin, however, did provide one great highlight during the series. On the first day, after Dick lost meekly to Wilding, McLoughlin and Brookes played the most sensational set of tennis that he, or anyone for that matter, had ever seen. The set was an entire match in itself featuring more games than any set in the history of the sport. McLoughlin was able to win it 17-15 on the strength of his famous cannonball serve and trademark grit and determination.

It was truly a time when Karl felt lucky just to be there on the team, just to be witnessing such a feat of physical endurance. He sat on the U.S. team bench, a sea of straw hats undulating right and left all around him, experiencing the greatest occasion yet in his sport’s history. It made Karl want to be a better player and a better man. Sometimes matches could do that to you. It was the marvelous thing about sports. Though the United States lost the Cup and he did not get a chance to play, Karl came away from the experience inspired to finish the season strong at Newport. He wanted to dig deep, make up for the slight at not being selected to play and show the kind of fight that Mac had, to be able to last to 17-15, or even longer, to win a set, if that was truly what it took.