By Randy Walker

@TennisPublisher

The USA-Brazil Davis Cup first round in Jacksonville this weekend provides the perfect platform to discuss what I feel is one of the most courageous Davis Cup stories that not a lot of people really know about.

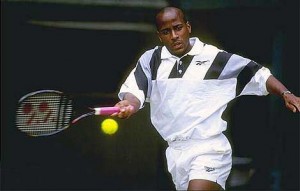

It just so happens to have occurred the last time the United States played against Brazil in Davis Cup back in 1997 and it involves, ironically, a Jacksonville resident, MaliVai Washington.

I called Mal on Monday this week and told him I wanted to write a column on how he should be awarded the Purple Heart award for U.S. Davis Cup duty.

“That’s a little dramatic,” said the modest and well-liked Washington when I presented him with my metaphor of his heroic Davis Cup effort against Brazil 16 years ago in a first-round match in Ribeirão Preto, Brazil.

Washington, however, wasn’t originally part of the selected Davis Cup team for the 1997 match with Brazil, despite having reached the Wimbledon singles final the previous July and having represented the United States at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, falling one match shy of the medal round.

U.S. Davis Cup Captain Tom Gullikson, in a high-profile press conference at Madison Square Garden in New York before an exhibition called the Nike Cup, named No. 8-ranked Andre Agassi and No. 16-ranked Jim Courier as the U.S. singles line-up and Alex O’Brien and Richey Reneberg for the doubles.

To prep for the slow red clay in Brazil, Captain Gullikson, also the head of USTA Player Development at the time, conducted a mini-camp at the USTA Player Development Headquarters at Crandon Park in Key Biscayne, just before departing for Brazil. However, shortly after the camp began, Agassi decided to pull himself off of the US team. Agassi’s play – and perhaps his mental attitude – was not up to his standards and he, to the surprise of Gullikson, decided to beg off. As he documented in his autobiography “Open,” the 1997 season turned into a low point emotionally and professionally for Agassi as his ranking dropped from No. 8 to No. 141. Gullikson then made the call to Washington to join the team.

“I was actually at the ATP Headquarters in Ponte Vedra when I got the call from Gully,” said Washington, ranked No. 24 at the time “For me, not having the opportunity to play a lot of Davis Cup, because of the great players we already had, I jumped at the chance. I had had the chance to play a few times before but to have the opportunity to play is pretty special.”

So after a morning workout on the hard courts in Ponte Vedra Beach in anticipation of next playing the next ATP event in San Jose, California, Washington hit the clay courts that afternoon to get his clay game ironed out to take on the Brazilians in only his third appearance on the U.S. Davis Cup team.

The Brazilian team set to play the United States was led by Fernando Meligeni, who had posted a fourth-place finish at the Olympic Games the previous August, but the second singles player was a young up-and-coming 20-year old named Gustavo Kuerten, who had just cracked into the top 100 in the rankings for the first time, ranked No. 85.

On the first day of play, Washington was set to open the best-of-five match series against the young Kuerten, who Washington said he “wouldn’t have been able to pick out of a two-man line-up” prior to that week in Brazil.

“At the beginning of the year, you go down to Australia and you look at the qualifying draw and the main draw and there are always a handful of players who maybe you have heard of and maybe you haven’t, but there is always a crop of player who are early out on the tour,” Washington said. “Back in 1996, I had heard of Kuerten. He had had some results and cracked the top 100 by the end of 1996. I heard of him, but I didn’t know anything about him. I had never seen him play. Honestly, I didn’t know who he was.”

Kuerten was ranked 61 spots below Washington, but playing him on Brazilian red clay, under a hot sun and in high humidity that he was more accustomed to, with a boisterious crowd treating the tennis match as if it was a Samba party, was no doubt a challenge.

“You’re going out on the court a little blind,” said Washington. “In Davis Cup, in Brazil, on clay, against a guy who is starting to have some pretty good results, but I certainly went into the match thinking I am the better player and I should win this match. I was ranked higher and I had had some pretty good results recently. I went into it thinking I was favored in that match. Little did I know or would anyone know, that just a few months later he would be moving on and winning the French Open, which is kind of strange and scary to actually see.”

Kuerten came out like gang-busters against Washington, stroking the one-handed backhand that would go on to be regarded as one of the best in the history of the sport to near perfection. He took the first set 6-3 and was points from taking a two-sets-to-love lead, with Washington winning the second set in an 8-6 tie-breaker. The third set would also go to a tie-breaker and, with Washington leading 5-3, something strange happened. Washington said that he started to feel a sharp pain in his left knee. He played through it and secured the crucial two-set-to-one lead with a 7-3 tie-breaker win, but he was concerned about his condition.

Washington would watch the tie-breaker on video later and looked closely at his knee to see if there was some trauma that caused his injury, but he could not see anything. Starting at the beginning of the fourth set, the U.S. Davis Cup medical team loaded Washington up with ibuprofen and ice for his knee. Washington continued to slug through the match, despite the pain.

“You have your teammates there pulling for you and yelling for you, there’s no sense of giving up,” said Washington. “There is no part of you that is going to quit. Short of literally snapping an ACL, there is no quitting.”

The will to win for his country, his teammates and the screaming but small U.S. Tennis Association contingent engulfed in a sea of fanatical Brazilians fans was too strong. Washington was not going to be denied.

“I just kind of managed to get through that fourth set solely on adrenaline I believe,” he said.

Washington’s 3-6, 7-6 (6), 7-6 (3), 6-3 win over the future three-time French Open champ gave the United States a key 1-0 lead with the momentum.

“It wasn’t until after the match that I fully realized how bad things were in my knee,” Washington said. “I remember right after the match, being in the locker room, and not being able to squat down and pick up a ball. I literally could not squat down without feeling the sharpest pain in my knee.”

When I asked Mal if he would have pulled out of the match with Kuerten if it was a regular ATP event and not a Davis Cup match. He responded without hestitation. “Oh God yeah.”

While Washington was in the locker room, icing his knee and preparing to do press interviews, Courier was also engaged in an all-out clay court battle with Meligeni, that the American squeeked out in five sets 3-6, 6-1, 6-4, 4-6, 6-4 to give the U.S. a commanding 2-0 lead after the first day’s singles.

In the Saturday doubles match the next day, the U.S. was hoping to close out a 3-0 shutout with O’Brien and Reneberg taking on Kuerten and Jaime Oncins. However, the Brazilians steamrolled the shell-shocked Americans 6-2, 6-4, 7-5 to cut the deficit to 2-1. The final day reverse singles would feature one, perhaps two live matches.

Washington, who was scheduled to play Meligeni in the fifth and decisive singles match if it came down to that on Sunday, tested the knee in a short practice session with Captain Gullikson Saturday.

“I remember the next day, going out and trying to hit some balls,” Washington said. “I had no lateral movement. I was probably on the practice court for five minutes and Gully and I decided right there that there was no way I was going to be able to play the next day. That’s when he decided he needed to talk to Alex O’Brien and get him ready for singles on Sunday.”

Courier was to play Kuerten in the fourth rubber to try and clinch the win for the U.S. and if Kuerten was able to upset the two-time French Open champion, the match would be decided by the final singles match between Meligeni and O’Brien, a Davis Cup rookie playing a deciding fifth match on, perhaps, his worst court surface in front of a hostile crowd.

Washington said Courier likely treated his match with Kuerten as though it was a deciding match of the series, not knowing how O’Brien would handle the situation if it were a live fifth match. However, as he had done so many times in the past – and as he would do again in the future – Courier rose to the occasion and played one of his most classic Davis Cup matches, beating Kuerten 6-3, 6-2, 5-7, 7-6 (13-11).

“That match against Meligeni on Day One and against Guga on Day Three, those were typical dogged, never-give-up, will-ourselves wins,” said Washington. “I think Jim realized that we were going to ask him to step up even more to close out that match in the fourth rubber. He realized that clay courts were not Alex O’Brien’s best surface and putting Alex against Meligeni in that fifth match was going to be a heck of a task, if it came down to that.”

With the match secure by a 3-1 margin, O’Brien won the dead rubber over Meligeni 7-5, 7-6 (4) to make the final score 4-1 for the Americans. Kuerten left the series with some valuable match experience that would carry him to winning the French Open out of nowhere as an unseeded player five months later. Washington left Brazil with a good deal of concern regarding his knee.

“I had gone from San Jose to Los Angeles to Miami to have my knee looked and no one could tell me what the issue was,” said Washington. “I was resting it and icing it and it was able to hold up for a short period of time. If you look at my results right after that, I was winning some first round matches, but then my knee would give out and I couldn’t last beyond a match. Honestly, if players would just move me from side to side, they’d beat me, but guys weren’t figuring it out right away.”

Washington lost in the first round of Memphis and Scottsdale and pulled out of Indian Wells and Miami. He was able to muster two wins in Chennai, India, but after winning only three games in a first round loss to unheralded Martin Rodriguez in the first round of the U.S. Clay Courts, Washington knew something had to be done.

“There was a point in April, I remember just saying ‘I am not going to play another match until someone can tell me what’s going on with my knee,’” said Washington.

Washington soon went under the knife. He described it as “microfracture surgery” to cure a condition called Chondromalacia, which is kind of a bone bruise. The condition develops due to softening of the cartilage beneath the knee cap, resulting in small areas of breakdown and pain around the knee. Instead of gliding smoothly over the knee, the knee cap rubs against the thigh bone or the femur, when the knee moves.

“I remember getting out of surgery and the doctor said there was about a 30 to 40 percent chance that I’ll play professional again,” said Washington. “That was a big surprise to me. I always had this idea that you go in, you have knee surgery, you work your tail off, you rehab, and you get right back out there. Then he’s telling me there is a less than 50 percent chance that you will get back out there and compete again. To me, (what the doctor said) was kind of just words. I didn’t buy it because I knew that I would be willing to put in the time in rehab and get back out there.”

Unfortunately, for Washington, four to six weeks of rehab that was predicted by the doctor turned into eight months, causing him to miss the remainder of the 1997 season.

Washington then started again anew in the 1998 season in Auckland, New Zealand, where he managed to beat Marcelo Filippini in the first round, before losing 6-0, 6-4 to Byron Black. At the Australian Open, he managed a four-set win over Radomir Vasek in the first round, but the pain in his knee was too great to continue and he withdrew from the tournament before his second-round match with Francisco Clavet.

“At that point,” Washington said, “I felt like my career was over. After you go through eight months of rehab and then you play a couple of tournaments, it felt like my knee felt as bad as it ever felt. That’s when I went back, visited more doctors, had it looked at again and proceeded to have another surgery, this time out in Colorado with Doctor (Richard) Steadman and had the exact same surgery on a little different part of my knee. Adjacent to the where I had the old surgery.”

Washington rehabbed the knee again and returned to tennis in July after a three-month hiatus, but said “it was just never right.”

“I think after the first surgery, I felt like I had the opportunity to come back and play at the level that I had always played at,” said Washington. “Knowing what I went through after the first surgery, and how tough that was, after my second surgery, trying to get back to where I was even in my head. It was more of a let’s just see if I can get back on the tour and compete at pretty high level and continue to do what I love to do. I kind of quickly realized that that was not even going to be possible.”

Washington tried to give it only final go in 1999, but his comeback match at the Hall of Fame Championships in Newport against a young Harvard student named James Blake ended in defeat, the future U.S. Davis Cupper winning his first career ATP Tour level match.

Washington said that it became almost a relief when he finally realized that the knee injury sustained while representing his county would cause him to retire.

“For the better part of two years, how my day went was contingent on how my knee felt,” Washington said. “If my knee felt good, I could have some success on a tennis court. If my knee did not feel good, I was likely going to lose. Once I made the decision to retire, my day was no longer contingent on how my knee felt, so it was a relief.”

“It takes a lot to get to that point, that you are OK with retiring,” he said. “And you are ok with retiring under circumstances that you are not happy with. I think that was what was going on a lot in 1999 – hoping I could get back there and rehabbing and doing all of that, even in the back of my mind, I knew it was a long shot.”

Now Washington spends most of his time and gains the most satisfaction from running his Jacksonville-based foundation The MaliVai Washington Kids Foundation (www.MalWashington.com) established to promote academic achievement and positive life skills in Jacksonville among youth through the sport of tennis.

“I am trying do everything I can to get young people in the inner city of Jacksonville to do what I can to keep them on track and get them to understand the importance of education and getting them to set goals and think outside of neighborhood and schools and to realize that there is so much opportunity out there,” he said. “Fortunately, what we are doing is working. We have a lot of youth succeeding and achieving more than they otherwise would be.”

While reaching the Wimbledon singles final, representing the United States at the Olympic Games and Davis Cup and reaching the top 10 in the world are accomplishments Washington can be proud of in his career, it is his work with his foundation that gives him the most fulfillment.

Said Washington, “As much as I thought my calling was to play tennis, I think now I have the ability to impact a lot of people beyond playing tennis and affect a lot of lives, which I think ultimately that is going to have a great impact on people and have a greater impact on the world than me ever hitting a tennis ball.”