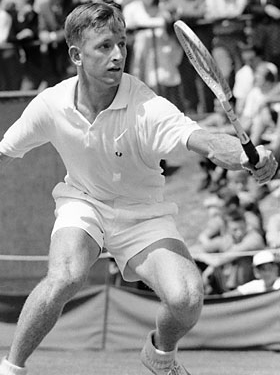

It was 48 years ago on Friday, May 28, 2010, that Rod Laver was down his only match point in either of his two historic Grand Slam runs (1962, 1969). In the quarterfinals of the French Championships of 1962, Laver faced fellow Australian Marty Mulligan, who nearly turned the tide of tennis history with one swing of the racquet.

Here’s how Laver recollects the famous match in his newly updated and re-released memoir THE EDUCATION OF A TENNIS PLAYER($24.95, New Chapter Press, www.NewChapterMedia.com), co-written with Bud Collins.

I realized that this was the hardest championship for me to win, and because of that it probably meant more than the other three. It was certainly the toughest in 1962 when either Marty Mulligan, an Australian who revels on clay, or Roy Emerson should have beaten me, and Neale Fraser could have. Those were three straight five-set matches beginning in the quarters with Mulligan. Fraser in the semis went to 7-5 in the fifth, and Emmo in the final won the first two sets before I began to wear him down. Mulligan—or Martino Mulligano, as his pals sometimes call him now—had the best chance, leading me two sets to one and holding a match point in the fourth set.

How do you make an instant Italian out of an Australian? Add two o’s and stir some remote Italian blood in the genealogical pot. We kidded Marty about his conversion to the Italian Davis Cup team in 1968, but he was only doing the best he could with his tennis talents and nobody blamed him. Marty came out of Sydney and was a mate of mine on the Australian Cup team of 1959.

He’s a little fellow, very steady, and he took to the European clay better than he did to his native grass. His strokes were accurate and consistent, but he lacked the booming game that intrigued Harry Hopman, our captain. He also came along at the wrong time, in the midst of some of the best tennis players any country has developed. So Marty wisely moved to Italy to live. There he went on the payroll of a large club in Milan, becoming available for the interclub matches, very popular in Italy. The Italian clubs buy players from all over to compete in these “amateur” affairs.

Marty fitted well in Italy, learned a few words, fell in love with an Italian girl, and accepted a bid to play on the Italian Davis Cup team. Since he’d never competed for Australia, he was eligible, after declaring himself a resident. This caused a furor in Italy. One faction, backing Marty, wanted only to win, like the Americans in 1958 who broadened the Good Neighbor Policy to include Alex Olmedo of Peru on the U.S. team. But an opposing faction was horrified to think that an Australian would take the place of an Italian boy in representing the homeland.

All Marty wanted to do was play tennis and make as much money as he could. Europe was the place to do that in the amateur game, and he could make even more by playing for Italy, probably as much as $30,000 a year all told, with very favorable living conditions too. Luckily, he discovered an Italian grandmother in his family tree. She had immigrated to Australia. That made it reasonably okay, and Martino Mulligano wore the insignia of Italy in 1968, for one year. Italy wasn’t able to win the European Zone, so Marty was dumped. They figured they could lose just as easily with full-blooded Italians.

But this was in 1962 when we played. He was just plain Marty Mulligan, promising young Australian—and he was one point away from cancelling out that Grand Slam. I was down two sets to one and serving at 4-5, 30-40, the only match point against me in either Grand Slam.

It’s hard to get a bunch of Frenchmen excited about two Australians playing tennis, but I was the favorite, the top seed, and here was this nice-looking nobody named Mulligan about to pull the big upset. Momentarily the customers adopted him as though he were St. Martin, the Patron Saint of France.

If Charlie Hollis had been there, he’d have screamed: “Get your first serve in!” It was the only thing to do in a tight spot, and I got mine in all right—into the net. So now I was down to the second serve. I spun the ball to his backhand and came sprinting in to the net behind it. Maybe I should have stayed back, but all through the match he’d been sending his backhand return down the line, and I wanted to move right to the spot and cut off the return. Sure enough, he stuck to the pattern, and I was there to bang a winning volley. It was deuce. The match point was gone, and I held serve for 5-5. I was still in there, but Marty was fighting hard to close it out in four sets, and the crowd let him know they felt that way too.

The set stretched to 8-all, and then a linesman’s eyesight was questioned by Marty, and this quiet, polite Australian erupted uncharacteristically. He was serving and I hit an approach shot that sailed over the baseline. At least Marty thought so, and I’ll take his word for it. His word didn’t count, only the linesman’s who said the ball was good. My point.

This was too much for Marty. He began screaming at the man on the line and the umpire. I was shocked. I’d never heard him raise his voice before. Then I was stunned as Marty picked up a ball and smacked a high-speed drive at the linesman. The fellow’s eyes were definitely all right; he ducked, avoiding a headache at the least. The ball hit the grandstand loudly and rebounded across the court.

Marty wasn’t the only one shouting now. The umpire was shouting back. Neither understood what the other was saying, but they didn’t need an interpreter for most of the remarks. The referee marched out to try and stop the argument. You’d think I’d written the script, the way things worked out, but I stood by uncomfortably until Marty got it all out of his system.

When we resumed he’d stopped complaining, but he’d lost his concentration—and he’d lost his followers. Suddenly he was no longer St. Martin to the crowd, and they began jeering him. They had been carrying Marty but now they got on his back, and he couldn’t resist that load. I won eight of the last ten games.