by Joseph B. Stahl

If you remember nothing else, remember this:

“When Lew Hoad was at his peak, nobody could touch him.” – Pancho Gonzales (Hoad’s greatest rival)

“If Lew Hoad was on, you may as well just go home or have tea, because you weren’t going to beat him.” – Don Budge (rated by many the greatest of all time [with a wood racket])

“Lew Hoad could do anything he wanted to with a tennis ball.” – Gene Mako (Don Budge’s doubles partner)

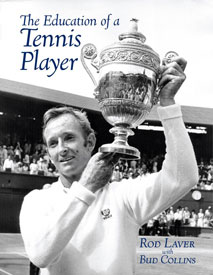

“Lew was my idol both on and off the court, and he once beat me 14 matches in a row, even though he had a bad back.” – Rod Laver (also rated by some as the greatest of all time [wrongly] with a wood racket)

“If Lew hit the ball any harder it would burst into flames.” – Budge Patty (who won the French and Wimbledon in 1950)

“When Lew felt like playing, man, he was really something. I never saw anybody who could snap the ball back hard off both sides from way behind the baseline for winners the way he did.” – Jack Kramer (another “greatest” contender, of the wood men)

“Think of the greatest tennis match ever played, and the chances are that Lew Hoad was in it, and won it, and shrugged it off with an understatement. Rod Laver was a carbon copy of the original Hoad, but without the awesome majesty, without the mighty power.” – Gordon Forbes (in A Handful of Summers [1979])

“Lew’s tennis was so great that he thought he would always be in Heaven, but he had no business sense, and in the end lost all his money.” – Pancho Segura (from whom Lew said he learned more about tennis than from anyone else)

It’s hard to know how truly great Lew was if you never saw him, because the fixture-tournament record books won’t tell you. Three things conspired to undermine his record in those events:

1) The amateur-professional split that endured from 1926 to 1968 and banned the pros from the fixture (major) tournaments; Lew turned pro after winning the amateur Wimbledon for the second year in a row in 1957, and when tennis went open 11 years later his career was already over;

2) Severely debilitating back trouble that recurred intermittently starting in his amateur days and continuing during his professional years; it was ultimately diagnosed as two herniated intervertebral lumbar discs, a condition that would prevent most people from even walking; and

3) An easygoing personality that, even when he was healthy, put no premium on winning and was never sorry about losing; friendship with his tennis buddies (players in his day depended on each other for a social life, unlike today) seemed more important to Lew than beating them, which made his performance inconsistent and occasionally marred his record with losses beneath himself—he was a very up-and-down player; but everyone loved Lew Hoad, and Jack Kramer said of the surly and irascible Pancho Gonzales (who hated almost everybody), “When Lew Hoad dies they should put on his gravestone that ‘Even Pancho Gonzales liked him,’ ” which I can personally verify was true.

According to both Tilden and Kramer, day in and day out Budge was the greatest of the wood men , but even they admitted that when Vines or Hoad was “on” Budge could not beat them, it’s just that Vines and Hoad weren’t consistently “on.” Kramer and Gonzales are also contenders for greatest of the wood men. I saw them, never did see Budge or Vines (except in movies), but it’s a safe bet that if you put Vines, Budge, Kramer, Gonzales and Hoad in a dice shaker and threw them down on the table, one of them would definitely be the greatest ever of the wood men. As a person, though, Lew is my favorite. The guy was unspeakably wonderful. He could come up with remarks that would torture you to death with laughter. And he was a superlatively decent human being.

At Wimbledon in 1957 Hoad beat Ashley Cooper in the final in less than an hour. “Coop,” whom Lew described as “my best mate,” would win the title the following year, with Lew away in the pro ranks.