Who is the greatest tennis player of all time?

Who is the greatest tennis player of all time?

This is a question that is discussed almost daily in the tennis world. But how does one compare players from different generations? How would Pete Sampras fair against Don Budge or Jack Kramer or Bill Tilden? What about Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal playing against Rod Laver or Ivan Lendl?

There was one tennis insider and Wimbledon champion who had a unique perspective on all of the all-time greats in men’s tennis mentioned above in that …he saw them all play! The man is Sidney Wood, who before his death in 2009 at the age of 97, wrote about and compared the greatest players of all-time and documented his thoughts in writing, that was published in 2011 in his post-humously published memoir called THE WIMBLEDON FINAL THAT NEVER WAS…AND OTHER TENNIS TALES FROM A BYGONE ERA ($19.95, New Chapter Press, available here: http://www.amazon.com/dp/

Wood’s chapter called “Analyzing the Greatest Players of All Time” is excerpted below…

******

Bill Tilden vs. Pete Sampras or Andre Agassi? Given today’s immensely more power-packed racquets, who would pick up the marbles? And how about Rod Laver, Don Budge, Fred Perry, Jack Kramer, Pancho Gonzales, René Lacoste, Henri Cochet, Jean Borotra, Ellsworth Vines, Bobby Riggs, Lew Hoad, Tony Trabert, Frank Sedgman, Ken Rosewall, Arthur Ashe, Jimmy Connors, Bjorn Borg, John McEnroe, Boris Becker, Ivan Lendl or Stefan Edberg?

Such questions are constantly put to every player whose repute and venerable status give credence to one’s observations, and even present-day tournament players and chroniclers of the game have an abiding interest in the player-comparison opinions of those they consider eminently qualified.

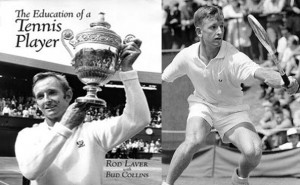

In fact, at an International Tennis Hall of Fame dinner at Newport a few years ago, Bud Collins, the globe-trotting tennis sophisticate, who was aware that I’d qualified for my first Wimbledon at the unlikely age of 15 in 1927, surprised me with the Tilden-contra-the-world question. He told me the sport of tennis was in need of a book by someone who had seen all the great matches and played “everyone” and that I was also the only guy still around who could first-hand compare and record what every tennis buff would hope to know. Computers now spit out weekly rankings of over 1,000 players on a weekly basis, but back when punch cards were its high-tech breadwinners, national amateur rankings were determined by committees appointed by each country’s tennis association (no more than fifty players were ever rated in the United States) and rankings of the world’s top 10 were decided by a succession of self-appointed London sports columnists whose judgments sometimes appeared based as much on favoritism as fact. Add to this the fact that from 1930, when “Big Bill” Tilden departed the amateur ranks, until 1968, when Jack Kramer led the pro contingent into the “Promised Land of Open Tennis,” the pros were barred from all major tournaments and excluded from the world rankings. This rendered the rankings meaningless as a measurement of the world’s best. Also prior to 1968, virtually every newly-anointed amateur champion would be lured to the pay-for-play game, thereby stripping the amateur ranks of its marquee drawing cards and permitting as yet unproven contestants to be crowned No. 1 in the world of “officially-sanctioned” tennis.

The effect of this double standard? Just tote up the number of stadium-filling superstars lost to the major amateur events through the schism: Tilden in 1931, Cochet in 1933, Vines in 1934, Perry in 1937, Budge in 1939, Riggs in 1941, Kramer in 1948 (following the five-year World War II gap) and, during the next two decades, Gonzales, Sedgman, Hoad, Rosewall, Trabert and Laver all bid adieu to the trophy-only circuit.

With each season’s cumulatively diminished quality of competition, the paths to Grand Slam glories were measurably eased for the succeeding year’s hopeful. Put another way, with Wimbledon as our focus, Tilden would have been the bettors’ favorite to garner another two wins; Budge, at least another four or five; Riggs, Kramer and Gonzales, three to five each. As for Trabert, Hoad, Rosewall and Laver, who knows how many among them? Pre-1968 winners such as Wood (ouch, that’s me!), Ted Schroeder, Yvon Petra, Vic Seixas, Jaroslav Drobny, Bob Falkenburg, Budge Patty, Dick Savitt, Ashley Cooper, Alex Olmedo, Neale Fraser, Chuck McKinley, Roy Emerson and Manolo Santana all would have been hard pressed to squeeze out even an occasional win against their abdicated amateur opponents.

Three all-important extenuations bear on the records of our brightest of stars and we must comment on their merits in order that the reader may interpret their relative importance, vis-a-vis the overall picture of the half century under review. For example, the first U.S. airborne wayfarers to Wimbledon and Paris were in 1946. Before that time, the boat trip to Europe was a five-day affair plus the absolutely essential need of a week to find your land legs. Each year you could safely predict that half the top seeds who would debark from the boat from Wimbledon to the United States to compete, usually the next day, in the Meadow Club tournament, and would be out of the singles after the first or second round, would be left to quench their frustrations on the sunny Atlantic sands of Southampton. All in all, it took about eight weeks to make the scene at both Paris and Wimbledon, while from Australia, this period was more than doubled. Often the trip was economically or otherwise unfeasible for the reasonably-pure amateur of those days.

The second consideration was the advent of World War II, which resulted in a six-year championship hiatus from 1940 to 1946 at Wimbledon, Paris and Australia; and, with most of the players in the service, there was a low-level entry at Forest Hills. In virtually every sport, leading athletes lost out on the opportunity to enhance their records during their prime competitive years. In tennis, this especially affected players such as Don Budge, Bobby Riggs and Jack Kramer.

The final consideration has to be the development of pro tour tennis, which lured the leading performers to its ranks and prevented their participation in the four major events and Davis Cup. Until 1968, these men were precluded from defending their Wimbledon, Forest Hills and other crowns by the simon-pure rules in effect.

When Rod Laver went pro in 1963, he was fresh off winning his first Grand Slam, in which he dominated and beat everyone in the amateur kingdom. But, here again, there was quite a way to go before he would become a case-hardened touring pro. Though there were to be no more head-to-head professional barnstorming matches, Rod met Gonzales in meaningful tournament matches over a two-year span but could win only a few. How would he have fared after more seasoning and the years had cooled some of Pancho’s fire, we’ll never know.

Also until 1968, Davis Cup regulations prohibited professionals from competing for their countries and over the previous ten years, during which there was high-purse pro tennis decimating the upper reaches of the amateur lists, the world’s best were not participating. This is sad for such a long-recognized important goodwill-builder among nations to be only a minor factor in the considerations of the player’s individual world ranking.

A fair question would be to ask where I get the gall to take on this project. At the age of 14, and almost 90 pounds, I won the Arizona men’s singles, which earned me entry to that year’s U.S. Nationals, the modern-day US Open. The following spring, I was shipped to Paris for the French Championships and shockingly won two rounds to become the youngest ever male qualifier for Wimbledon. There, I played defending champion René Lacoste on the hallowed Centre Court on opening day. In 1931, I became the youngest-ever Wimbledon men’s singles champion at the age of 19 (Boris Becker broke my record in 1985 when he won the title at the age of 17). From that time on, through to the late 1970s (doubles only towards the end!), I was privileged to compete against virtually every top player in the world. At the start of the organized pro game, I invented and patented the cushioned, transportable Supreme Court, which is still used for indoor events, and I was not displeased to be reminded by an old AT P buddy that there was no way the pro indoor circuit could have gone full bore had I not dreamt up the concept.

It is these years of experience and fraternal relationships that permit me to confidently assess the pecking order and relative aptitudes of my tennis brethren in our star-studded galaxy from nearly the dawn of competitive tennis, my aim being not to determine who belongs in any year’s top 10, but how the best would stack up against the best, in any year, past or present.

I’m positively no misogynist, so why would I not have included all those richly deserving ladies in this discussion? I have been present, or have viewed on TV, virtually all important women’s matches going back to the Helen Wills (Moody) era, and I do indeed have opinions as to which stars of the gentler gender belong on which rungs of the all-time ladder of tennis greatness. However, it would not only be more appropriate, but a better qualified assessment if such an analysis were undertaken by one of their own leading ladies who has shared the competitive scene.

My rankings are based essentially on win/loss records in important events, primarily the four majors – the Grand Slams – and the pre-1968, head-to-head pro tours, with appropriate credits accorded Davis Cup competition and other important events. What lies behind the printed scores is what determines the placement of each of the world’s great players. For instance, for many years certain tournaments have traditionally counted more than others. After 1946, when the top-amateur turns-pro system resumed, the purely pro events such as the U.S. Pro Championships, Wembley, and the WCT Finals in Dallas became important. Finally, judgments have to be made of the relative value that should be attached to such factors as longevity, consistency, two-man tour results and the ability to win on the slow as well as the fast surfaces.

The Top Fifteen

1. Don Budge: A no-brainer. In 1938, Don was the first winner of the Grand Slam and for six decades he has been recognized by his peers as the one player to have commanded not only every shot in the book for every surface, but also to have been blessed with the single most destructive tennis weapon ever—a bludgeon backhand struck with a sixteen ounce “Paul Bunyan” bat. All opposed? You might first want to check out Jack Kramer’s required reading, The Game. Jake knows all, tells all. Wrote Kramer in the book, published in 1979, “Don is still the best player I ever saw, and (Ellsworth) Vines is next. Right away a lot of people are going to say I’m an old timer, pushing the guys of my era. Don’t I know that the human body runs faster and jumps higher now than in the 1930s? And I say, yes, I know that, and will you please name me a better hitter than Ted Williams and a better singer than Caruso?… I feel fairly confident in saying that Budge was the best of all. He owned the most perfect set of mechanics and he was the most consistent…Day in and day out, Budge played at the highest level. He was the best.”

2. Jack Kramer: The choice is clear to me, but may be less so to certain of today’s forty to fifty-year-olds; but even a scan of Jake’s professional stats tells you why he was a rung above Pancho Gonzales (who in turn handled all the rest).

3. Bill Tilden: Most sports fans know Bobby Riggs (thanks in part to Billie Jean King, who beat him in the famed 1973 “Battle of the Sexes” match), René Lacoste and Fred Perry (their shirt labels!), but poor Henri Cochet, Jean Borotra, Pancho Segura—even Budge, Kramer and Gonzales!—are becoming shadowier with time and better remembered by historically disposed fans. But everyone has heard of William T. Tilden. In his day, Big Bill was as world famous as Jack Dempsey, Bobby Jones—even Babe Ruth! He changed the game’s image from a side-court chair, standing-room sport to a stadium- packed, crowd-pleaser (it was Bill who paid the freight on America’s first tennis stadium at Forest Hills). The press named his pile-driver first serve “The Cannonball” and, allowing for the transformation of tennis racquets, no one other than Frank Shields and Ellsworth Vines ever owned one better. Bill’s enduring record on every surface—an absolute master of every shot in the book—make him a shoo-in for third on my list. Were there more witnesses around who’d seen Tilden play everyone in sight until the age of 48, I might well be sued for leaving him off the top. In spite of his constantly troubled lifestyle, Bill, together with his mighty contemporaries, Jones and Ruth, must go in the books as a once-in-a-century sports aberration.

4. Pancho Gonzales: Other than for his nemesis Kramer, Pancho dominated the pro touring field after leaving the amateur ranks after winning the 1949 U.S. Championships. He had many one-sided win records against such Grand Slam event champions-turned-pro as Frank Sedgman, Tony Trabert and Ken Rosewall.

5. Rod Laver: He won the first of his double Grand Slams as an amateur in 1962, but in his 1969 win he had every active pro in the game to vanquish. His only significant tournament disappointment was his failure to win a WCT title, losing two finals to an inspired Ken Rosewall (their second match in 1972 was one of the greatest I’ve ever seen). There will understandably be many who can’t comprehend why I place a two-time Grand Slam titleholder midway among the first ten, but in my opinion, when comparing Laver’s strokes to these other great champions, this is the position in which I feel he belongs.

6. Pete Sampras: You know all about those weeks without end as numero uno, his multiple Slam record, especially his virtual ownership of Wimbledon’s Centre Court. His understandably respectful peers were resigned to playing second fiddle to Pete, but they looked forward to ambushing him on slow clay. But it is Pete’s inability to capture a single French Championship – perhaps to equate with Ivan Lendl’s frustrating naughts at Wimbledon – that puts a hold on marking him ahead of other unbeatables who’ve done it.

7. Fred Perry: Where do you put a player who practically waltzed through three straight Wimbledons and two of our national singles, plus an Australian and French for sweeteners? This, of course, is Fred Perry who did his winning when all the big guns except Vines were around to test him. After he turned pro, Fred played a 61-match neck-and-neck tour with Vines, 1936-37 (Vines won, 32-29), but he began to sag a bit thereafter (Vines beat him head-to-head 49-35 in 1937-38). Barnstorming was not this Britisher’s cup of tea, but he belongs at no less than number seven among the splendid ones.

8. Bjorn Borg: Bjorn practically toyed with everybody through an astounding six French Open wins, but none of us sage old timers gave him a chance to make it past the second round on Wimbledon’s fast grass. Yet overnight, our high-roller, backcourt habitue became a demon volleyer and for five consecutive years, he made mincemeat out of such grass-court winners as Ilie Nastase, Jimmy Connors and John McEnroe. Borg stood an impossible four to five feet behind the baseline to take first serves, but was so fast out of the blocks that few wide slices got past him. He was one hell of an athlete. Could he have continued his dominance on the hard courts of the US Open, Borg would have been a shoo-in to be ranked ahead of all others, but on the hard courts of Flushing Meadows, his second delivery lacked the weight to defend against McEnroe’s chip-and run-in tactics, and Bjorn had to settle for a runner-up role.

9. Ivan Lendl: To me, Ivan was an enigma wrapped in a Centre Court frustration. He’d gladly have refunded Wimbledon’s first prize guineas several times over for just one win, but his best chance was in 1987, when he lost to the lower-ranked Pat Cash. Lendl beat all comers hollow on everything but grass, so why couldn’t he make it? Unlike Borg, no matter how many hours he ultimately spent striving to become a volleyer, habit was too strong. On crucial points, he couldn’t bring himself to leave the baseline and rush to the net, where Bjorn never feared to tread. Nonetheless, with three US Open titles, three French Open titles and two Australian Open titles and an astonishing 11 runner-up showings at majors (totaling 19 Grand Slam tournament finals), how can he not rate an upper berth-spot.

10. Jimmy Connors: Jimmy won eight major singles titles and was an eight-time runner-up. He failed to win only in France where he was unable to capitalize on his flat-hitting power. I was among those who urged Jimmy to stop feeling he had to bury every ball from the baseline, but it wasn’t until his waning years in the big time that the light finally dawned. In his later years, he was a born-again net rusher, but think how many of those lost finals he could have converted to victories had he unshackled his game and groundstroke fixation a decade earlier.

11. John McEnroe: McEnroe’s most remarkable season was 1984. He lost just 13 games in two final-round, straight-set wins in major finals over Connors (Wimbledon) and Lendl (US Open). That’s incredible. At the French, he had Lendl nailed but admitted he blew it and lost after leading two-sets-to-love. If the TV could have been programmed to cut out all but John’s shots in play, you would have been admiring perhaps the most naturally gifted shot-maker ever to play tennis. McEnroe’s great record of three Wimbledon and four U.S. titles, plus four major runner-up showings, puts him high on our ladder, but with even a modicum of self discipline (and regard for our game’s image), I’d bet he could have traded his odorous court garbage for more than just a few more wins.

12. Boris Becker: I’ve had a personal interest in Boris and his career ever since 1985 when he cleaned Kevin Curren’s clock to take the first of his three Wimbledon titles while erasing my 54-year span of being its youngest winner. Boris had a serve with an affinity for the Centre Court turf. He can give you a heavy whack with both his first or second, or slice it with wicked deception. He won one U.S. singles title and two in Australia, but Roland Garros refused to succumb to his power game.

13. Roy Emerson: When Roy wound up on his serve, he looked as if he were bowing to Wimbledon’s Royal Box, which could be habit-formed from having accepted the winner’s trophy there successively in 1964 and 1965. Elsewhere he walked off with two U.S., two French and a mere six Australian singles titles. Although these were before the Open era of tennis (1968), don’t knock it. Roy had what it takes.

14. Stefan Edberg: Stefan is almost a throwback to bygone years when the big events were on grass and 80 percent of the game’s best were serve-and-volleyers. Edberg’s was not a big serve, but his sure-handed, superbly-reflexed and fearless net play won him two titles at Wimbledon, the US Open and the Australian Open, plus a runner-up showing at the French in 1989. How many more would be crowding his trophy room if he could have waltzed in behind such trenchant deliveries as McEnroe’s, Becker’s, Ivanisevic’s, Sampras’s and Krajicek’s? Double maybe?

15. René Lacoste: Inventor of the first ball-throwing machine, the metal racquet and, of course, the chemise Lacoste, René had a tennis game that was every bit as mechanical as his creative brain. As the leader of the Four Musketeers of the courts (with Henri Cochet, Jean Borotra and Jacques Brugnon), René combined his Maginot Line defense game with pinpoint angled, counter-attacking ripostes. His two Wimbledon, two U.S. and three French wins were against such toughies as Bill Tilden and his compatriots Cochet and Borotra.

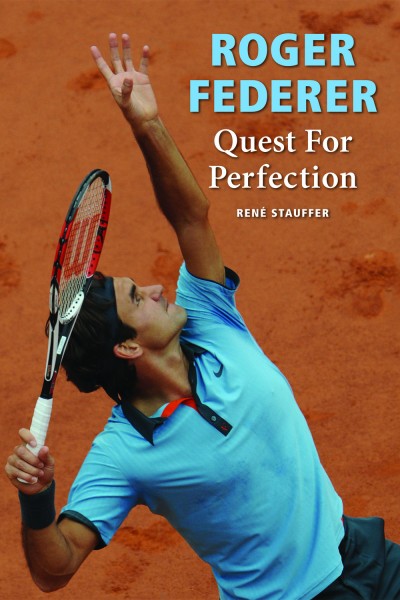

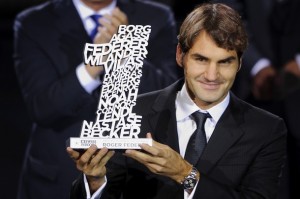

You might notice that there are some major omissions from this list of top 15 players of all time. Of course missing are the greatest players of the current era, Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal, as well as Andre Agassi, a winner of eight majors, including a career Grand Slam. My father was fortunate to have the opportunity late in his life to watch these three compete, but was not able to put his thoughts down on paper as part of this compilation. However, he was a big fan of all three players and would no doubt have place them in at least the top 10 of this list. Of Federer, he said he was the most intelligent player he had seen in over 50 years. Of course winning more major singles titles than any other man would place him near the top of this list. Unfortunately, my father passed away just months before Federer won the 2009 French Open that completed his career Grand Slam, and his record-breaking 15th major singles title weeks later at Wimbledon.

In addition to admiring Nadal’s ferocious physical game, my father admired Nadal’s great sportsmanship. My father came from an era in which sportsmanship was expected and the rule of the day. Nadal’s character and how he presents himself was not lost on him. While my father was not around to see Nadal clinch his career Grand Slam at the 2010 US Open, that milestone achievement would have rated him very high on this list.

Agassi was a player who grew on my father. When he first burst on the scene, my father detested his long hair and look – preferring the clean cut style of his own era. In fact, he would often go out of his way to not watch Agassi play. Through the years, however, he began to appreciate him more and admired his strength, speed and the way he played and took great joy in watching him in action. If Agassi’s final body of work (established after my father’s writing) is considered, he too would rank well against the players mentioned in this list, especially with his eight majors that included at least one each of the Big Four.

– David Wood