The match should get some consideration as one of the greatest of all-time. With all respect to this year’s Wimbledon epic between John Isner and Nicolas Mahut, it can be considered the closest match of all-time.

Forty-years ago this Sunday, on October 3, 1970, Cliff Richey and Stan Smith played in the semifinals of the Pacific Coast Championships at the Berkeley Tennis Club in Berkeley, Calif., with the winner of the match to earn the No. 1 U.S. ranking. The match was determined by one, sudden death point in a fifth-set tie-breaker. Winner take all. Richey, in his fascinating narrative book ACING DEPRESSION: A TENNIS CHAMPION’S TOUGHEST MATCH ($19.95, New Chapter Press, www.CliffRicheyBook.com) takes readers back to this epic match in this exclusive book excerpt.

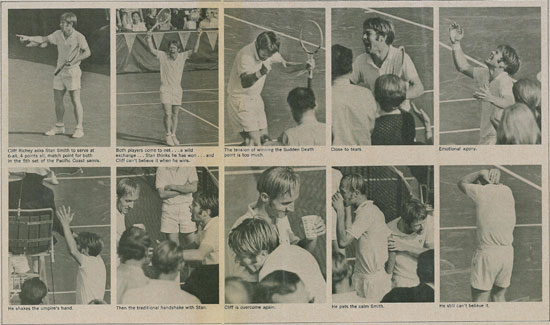

Saturday, October 3, 1970. The famous “Sudden Death” match.

Incredible as it may seem, the No. 1 tennis ranking in the United States rested on a single point. I was playing against Stan Smith at the Berkeley Tennis Club near San Francisco, California. The score was four points all, six games all in the fifth set.

It’s the only match I ever played where there was a simultaneous match point for both players. It can’t happen any more because they don’t use that kind of tiebreaker now. The nine-point tiebreaker was called “sudden death.” I always enjoyed playing “sudden death” tiebreakers, myself. I kind of liked them. I guess I’ve always liked to live on the edge.

We all knew the No. 1 ranking was up for grabs until the very end. Stan had beaten me two matches to one that year. But I had had a better year over all, and we were both ahead of all the other players. I felt like if I could beat him one more time, I would be ranked No. 1 in the country.

Stan and I had an emotional rivalry. We really didn’t like each other that well. We had high respect for one another, but I just hated losing to that guy. And vice versa. It was probably as much that as worrying about the ranking.

My sister Nancy, who was the top-ranked American woman herself in 1964, 1965, 1968 and 1969, helped me with my serve the day before. For most matches in general, I would not go out and practice my serve that way. But we both knew exactly what that match meant. She knew and I knew. I remember trying to wind myself up to go out there the next day. Stan had a serve-and-volley, attacking style of play. I was more defensive with my playing style. The match was on hard court. Everyone knew that the surface favored Stan. But I was better on fast surfaces than people gave me credit for. Nonetheless, the perception was that I was invading his bailiwick, his backyard. I knew I had to get a high percentage of first serves in. I needed to feel comfortable with my serve.

So Nancy and I went out the afternoon before to work on it. I got a basket of 40-50 used balls. I practiced my serve for at least an hour and a half. I knew I was running the risk of ending up the next day with a dead arm. But in my mind, if I had a bad day serving the next day, I would not win. My serve had never been my biggest strength.

In my characteristically obsessive way, I hit at least 200 practice serves that afternoon before. Nancy acted as another pair of eyes. She knew my game. What I tended to work on. I’d ask her if the toss looked high enough or if my shoulders were rotating into the court. She was an enormous help to me that day.

Going into the match, my mental state was good. I was coming down off of an unbelievably good year. I had won eight of the 26 tournaments I entered and was in the finals of five more. I was in the semifinals of eight or nine more still, including the French and U.S. Opens. A fellow player came up to me at the end of that year and asked, “Cliff, do you know how good of a year you just had?”

But as good as the year was, it was tiring. I don’t care if you’re young, you can still get tired. If you take just the one month leading up to that match, it was exhausting. Nonetheless, I had a lot of confidence. Emotionally, I was up.

So now we had just one more point to play. I missed my first serve. I threw in a little chicken-shit second serve. It was just a hit and a hope. The first order of business was just somehow to get the ball in the court. I came to the net off of that serve. He hit the return of serve. And then he came to the net! So we were both at the net! I dived for a backhand volley. I did a 360-degree turn. I just instinctually went for where I thought the ball was going to be. Stan thought he had passed me on the last shot, but I reached out and hit a winner. I hit a winning forehand volley. He still thinks it bounced off the wood frame of my racquet. I disagree. It certainly doesn’t matter now. . . . And then it was over. I was No. 1.

Stan recalls that right after that, I sort of went into a trance for about five minutes after shaking hands. I was in that “zone” people talk about. It was like I kind of flipped out or something. I was beside myself with excitement. I went back over to him and gave him a hug. After four hours, the winning score was 7-6, 6-7, 6-3, 4-6, 7-6 (5-4).

It was not my destiny for that to be my only “sudden death” experience. With emotional illness, a swift spiral downward can also seem like a “sudden death.” I used to say to Dad, “I’m the most blessed person I know. I ought to be the happiest person in the world. What’s wrong with me?” Dad would point to the wall and ask, “Don’t those trophies mean anything to you?” I would say, “No, they mock me.”

Perhaps I didn’t adjust well mentally as I went along. Eddie Marinaro, the football player, once said to me, “You’ve got the successful man’s disease.” When you have trophies hanging on the wall and a nice bank account and a nice house and no debts, but you still aren’t happy, you have to realize the problem might be with you. I made it to the top in tennis in all age divisions—midgets to seniors. I had major breakdowns all in between. While playing 1,500 tennis matches in 500 tournaments, I was like a fair-haired person who gets skin cancer from staying out in the sun too long. Genetically, I was predisposed for what happened, but circumstances also combined to produce my condition.

When I won that “sudden death” victory, I was at the top of my game. I had no idea at that point that I was already emotionally sick. I would have scoffed at the idea if someone had told me then, when I was 23, that my next 40 years would bear the stamp of clinical depression.