The U.S. Open is the last of the four majors in the calendar year, but only three-quarters of the roller coaster ride of professional tennis. Each day, players lose, players win and experience a wide variety of emotions in a sport where many of the competitors are in their early 20s and still learning to mature and grow into adults and still working out the travails of life.

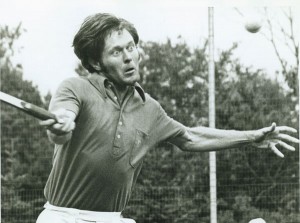

Cliff Richey was the best American tennis player on the planet 40 years ago in 1970 and experienced the same pressures of the modern pro tennis player. Richey discusses these emotional fluctuations in the context of his suffering from a disease that affects millions around the world – depression.

In this exclusive excerpt from the book ACING DEPRESSION: A TENNIS CHAMPION’S TOUGHEST MATCH ($19.95, New Chapter Press, www.CliffRicheyBook.com) written by Richey and his daughter Hilaire Richey Kallendorf, Richey discusses the pressures of tennis in this excerpt from the chapter called “Pressure Flakes.”

From 1964 through 1970, I didn’t worry about my skills too much. Success is as intoxicating as a drug. It just feels great. You get instant approval. The crowd hollers. They give standing ovations. You walk away with a trophy. You go back to the locker room, and everyone congratulates you. You get headlines in the next day’s newspaper. You have confidence in yourself. You’re on a roll. It’s all the affirmation that kids (and later, adults) want in life. There’s an adrenaline rush. It’s a real thrill. It feels like drinking about eight cups of coffee. Ecstasy would be putting it mildly. You feel lit up. You can’t turn off your motor. It’s revved up and it stays revved.

Once you’ve felt that, you want it again. You start chasing that next victory. Society puts its stamp of approval on winning. I’ve heard other athletes talk and they say once they retire, they can never find anything to match the thrill of the ball field. The cortisol, the “fight or flight” hormone, actually changes your brain chemistry. It also makes you more prone to disease: heart trouble, cancer, hypertension. You ride that crest during the “up” periods of accomplishment. You get addicted to the highs like a drug. I would like to know the percentage of how many ex-athletes become drug addicts and alcoholics.

At the start of the season in 1968, I pulled a rib muscle. It took a full month to heal. Once I could play again, I only had ten days to prepare for the U.S. Indoor Championships in Salisbury, Maryland. I beat Jan Leschly, Stan Smith and Clark Graebner to win the title. It was a huge win. But after winning the U.S. Indoors, I crashed very hard, very fast. It almost didn’t seem possible to sink that low after being so high. I’ve always experienced volatile emotional content. One of the problems with depression in general is that rather than recognizing it as a disease, you rationalize it as, “Oh, I’m just going through a difficult time right now.” That’s what happened with me after the U.S. Indoors. I would come back from a tournament, and it would take me 10 days to feel normal again. In hindsight, I think some of that was low-grade depression. Dad used to say: “As fit as you are, there’s something wrong if it takes you that long to recover.”

By the laws of physics, what goes up must come down. The cycle of competition and gearing up for a tournament fosters a crash after it’s over—much more than, say, a typical 9-to-5 job. There are performance anxieties, stage fright. With my drive and type-A personality, there was probably also a touch of bipolar there. When you lose a match, that insecure, anxious feeling takes away your self-esteem completely. You feel worthless. My drive for success on the court was in part a desperate attempt to ward off recurrent bad moods. I lived from one victory to the next.

I did let myself enjoy some of my victories on the tennis court. At least, I think so. But one of the bad things about any tour is, if you play more than just a few in a row, you’re never able to sit

back and enjoy it as much as you’d like. You certainly can’t enjoy it for very long. You know you have to get back to business, to begin training for the next one. I was always already thinking about the next match.

Normally, for a tournament, we had either a 32- or 64-man draw, so you had to win either five or six matches to win the title. That means you only had a few hours to enjoy each win. In that setting, if you don’t start immediately preparing for the next match, you’ll fall flat. Your job isn’t over. You have to play another one the next day, so you have to be disciplined. You don’t have time to gloat. You’d better not be thinking about your last win too long or too hard, because your matches only get tougher as you go.

“Adverse pressure” is the term Dad always used to describe the pressure to produce again once you’ve already succeeded. You can win two tournaments in a row and go on to the third and still have someone ask you, in essence, “What have you done for me lately?”

It’s like what I used to tell Jimmy Connors. Much later, in 1975, when we were practicing a lot together in England leading up to Wimbledon, he was feeling stressed out about defending his Wimbledon title. One evening over dinner I said, “Jimmy, here’s what you’ve got to do. You won it last year, and the trophy is in your trophy case. Now to win it this year, you have to psychologically take that trophy out of your case and put it back on the common shelf.

You ain’t defending shxx! The day Wimbledon starts, you’re competing for it all over again just like everybody else.” The up side to anxiety, if there is one, is that it drives you toward success. The moderate down moods even help too (they call this dysthymia, or low-level depression) by motivating you to get out there and succeed in order to feel better. You learn to counteract pain with the tonic of success. When dysthymia hits you, it drives you on. It tells you that you aren’t very good. You try to smother feelings of inadequacy by being creative and successful. Even when you win, that insecurity keeps telling you: “You still aren’t good enough.” It propels you into wanting to become even better. I had no bad depression before the age of 22. Perhaps that was at least partly due to the fact that up to that point, I had experienced very few losses. I still won most of the time. In 1969, I had some depression and some anxieties that were just awful. The absolute stark depression wasn’t there at the beginning, but there were some early warning signs: nervousness, extreme highs and lows, severe irritability.

It was a good year, play wise. In fact, it was the second-best year of my career. Winning the Canadian Open—beating Butch Buchholz in the final—was the highlight. The entire year was pretty much around-the-clock training and playing. If you’re playing well, you’re playing five matches a week. I always liked to be on the go. I’m an A-type. I have a lot of nervous energy. I think people with type-A personalities are, in general, more prone to depression. I have the agitated kind of depression, where your metabolism actually speeds up.

I also bite my nails. It’s a nervous habit. All the stress I was experiencing that year started to manifest itself in my sleep. I used to have very vivid dreams of winning one of the four Grand Slam tournaments. They felt so real that when I woke up, I was disappointed. I used to have a recurring dream where I was in the locker room, getting my court bag together. I was in the process of putting my tennis clothes on, or maybe taping a finger. All of a sudden, it would be just before the start of the match and I couldn’t get out of the locker room! They finally had to default me. That was one of my frequent anxiety dreams. In all probability, it was during those sorts of dreams that I first started grinding my teeth. It was during that period that I was diagnosed with temporomandibular joint syndrome, a jaw disorder known as TMJ. I clenched my jaw so hard, it started to crack my teeth. I had to get crowns. I sustained a lot of dental damage before it was properly treated. Most of the teeth in my mouth are cracked.

During the daytime, when I played tennis, the stress started to manifest itself in other ways. When I’m excited, my eyes get so big, they look like they’re about to pop out of their sockets. My eyes would dilate from the excitement of battle. I also tended to hyperventilate, another classic “fight or flight” response. Hyperventilation can produce leg cramps, because your system gets permeated by too much oxygen. I had those quite a few times in my career.

Cramping is an awful thing. It can hit you out of nowhere and basically incapacitate you. Any type of inactivity, a 10- or 15-minute break, can make the muscles start to spasm. I learned never to go into an air-conditioned locker room during the break between sets, because the cold air can also make you cramp.

But just because I was cramping, that didn’t mean I gave up. Only once did I not keep playing and finish the match even though I had muscle cramps. That happened in Paris. I was cramping so badly, I couldn’t even stand up! Five guys had to lift me up like a piece of lumber and carry me away. A little later in my career, when I was in the process of winning a five-set final match in Fort Lauderdale in 1971, I started to get leg cramps during the fourth set. Someone suggested to me that I should try breathing into a paper bag. I followed that suggestion, and it actually helped. The newspapers had fun with that incident as one of the headlines read: “Richey Paper-Bags it to Victory.”

A lot of amateurs think that if you put yourself under the heat enough times, eventually you get to a point where competition doesn’t vibrate your soul. That you get to a point where you’re not nervous any more. Well, guess what? It’s not like that. I played 1,500 competitive matches in 500 tournaments over 26 years. You get “up” and nervous for every single match—out of fear. Each one is life or death. You’re never immune to that pressure.

I’m a competitive person. That’s what I do. It would almost be more surprising if I didn’t scare people. You don’t just turn into this nice, friendly, non-combative, congenial person during your off time. It’s still bare-teeth competition. Mickie’s kid brothers used to say I ate “pressure flakes” for breakfast. If I could have found some, I would have eaten them, that’s for sure!

The tour was an escape mechanism, in a sense. It gave me places to go, places to run from my troubles and worries. Anxieties have a lot to do with constantly being on the move. That’s the definition of anxiety. You constantly feel like you could be doing more. Anxieties also create self-doubt. I practiced more than most people because I constantly doubted my abilities. Insecurity is a double-edged sword: it makes you more productive, but it also slices you up into tiny little pieces. You’re like a frog in a pot of boiling water. When the temperature is turned up, at first, you don’t notice; but the next thing you know it, baby, you’re cooked!