It has been revealed that a Wimbledon champion played a final at the French Championships while drunk.

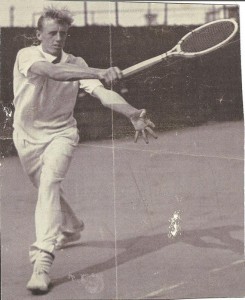

The player is Sidney Wood, the Wimbledon champion in 1931, who, unexpectedly and forcibly found himself inebriated. Wood tells the tale – one of many stranger-than-fiction stories – in his posthumously-released memoir called “THE WIMBLEDON FINAL THAT NEVER WAS ($15.95, New Chapter Press, www.NewChapterMedia.com), released this month.

The book details the life and times of Wood with a focus on one of the most unusual episodes ever in sport when he won the men’s singles title at Wimbledon in a default – the only time in the history of The Championships that the men’s singles final was not played. Wood, who passed away in 2009 at the age of 97, tells the story of how he won the title over Frank Shields, his school buddy, doubles partner, roommate and Davis Cup teammate – and the grandfather of actress and model Brooke Shields – when Shields was ordered by the U.S. Tennis Association (USTA) to withdraw from the final to rest his injured knee in preparation for an upcoming Davis Cup match for the United States. He then discusses his “private understanding playoff” that saw his match with Shields at the Queen’s Club tournament final in London three years later be played for the Wimbledon trophy. Wood, who could be called the greatest story teller tennis ever had, also relates fascinating anecdotes and stories that involve famous personalities from Hollywood and across the globe. The excerpt that details Wood’s inebriated final-round effort is found below.

At the age of 13, I was so skinny that of all the young hopefuls at the Berkeley Tennis Club in California, I was the only one who could stick his hand through the hole of the tennis ball discard box and squeeze out the most luscious of the slightly-used spheres. Although the box was a repository for donations to the YMCA and other worthy causes, I recall having no qualms about providing for myself and my fellow teeners.

My clear conscience may have been the result of long unrequited services as ball boy to the lady world champion, Helen Wills, later Helen Wills Moody. “Queen Helen,” a media title that her unbroken string of victories well merited, never had to worry where her next tennis ball was coming from, and it never dawned on her how desperately I coveted even one out of the half dozen that she would use for every practice session. The discards were always good enough to have their Spalding or Wilson names still visible on the felt, and to any sub-junior who has played a lot of sets with only the rubber undercover remaining, they were precious pearls. Six years later as the previous year’s Wimbledon winner, in one of those stranger-than-fiction tales, I found myself as Helen’s requested mixed doubles partner for the French Championships in Paris. Alas, however, for “reasons beyond my control,” our French title victory was denied by Napoleon…Napoleon brandy, that is.

The afternoon of our mixed final, I first had to meet the rock-steady René Lacoste in singles, losing to him in an unreal five-and-a-quarter-hour, five-set grueller on a searing, 98-degree afternoon (one of the longest matches ever played in fact). Afterwards, we were laid out on adjoining locker room tables, and in seconds the cramps were jumping all over us.

They hit me everywhere, the worst of my life. As René and I writhed and groaned, Fred Moody, Helen’s husband, appeared with a pair of double Courvoisiers, Fred’s remedy for many ailments. He carefully trickled one down my throat, but René, an abstemious Prometheus to the end, turned his down, and Fred dosed me with that one, also.

Then, in walks Pierre Gillou, the tournament’s referee and head of everything tennis in France, all hands and shrugs, to announce that despite his minutes’ earlier assurance (before my brandy medication) that the mixed doubles final had been rescheduled for the next day, it was now to be played immediately. Queen Helen, at that point in her life, was the most self-centered of champions imaginable, as well as being every tournament’s prime meal ticket whose every wish was a royal command. In America, she was every bit as famous as Babe Ruth or Jack Dempsey, and internationally more so. Possibly Helen was unaware that René and I had barely made it off the court on our own legs (and certainly of my brandy-benumbed condition). In any case, Gillou said she flatly refused to play the ladies’ singles and mixed finals on the same, next day for fear of being overtired before Wimbledon’s opening day, two weeks later, and Gillou capitulated.

After five humidity-draining sets, you have no idea how even a short snort can hit you, and I was now feeling no pain and ready to joust with Bill Tilden, Henri Cochet and Fred Perry, all at the same time. So, with no one around with enough sense or initiative to restrain me from doing something idiotic, I told Gillou I’d be on the court in minutes. I then headed for the locker room and, as I was struggling into my long gabardines, I conceived the brilliant idea of inserting two Dunlop tire ashtrays under my belt to support my undulating midriff muscles.

Thus accoutered, I descended to the pit where Fred Perry and Betty Nuthall were our intended victims. Also on hand was a stadium-packed gallery (the bleachers were always jammed for Helen). At net, rallying with Betty, I was not encouraged to see more than one ball coming at me at the same time, and it seemed best to select one to hit and let the others pass. Knowing me as a serious competitor, Betty no doubt assumed that I was clowning a bit – for which I was also known. But my pal Perry, who couldn’t believe I was still standing after my marathon, came up to net to ask if I were okay. I said, “I’m smashed,” and retreated to the baseline to try a few serves.

My muscles were no less done in, only anesthetized by Mr. Moody’s two double shots, and when I tried to toss up one of the three balls, it wouldn’t come loose. The ball stuck in my fingers and I could not put up a toss to hit a serve. We had won the toss and I told Helen she would have to serve first, and it was 0-3 when I finally had to step up and serve. Amazingly, the ball left my hand, made contact with my racquet and actually landed in its intended service box. Heading for net, I felt a little bump on my shoe and observed one of the ashtrays that had dislodged itself, dropped down my trousers and was rolling along with me. Play was called by the umpire to remove the alien object. To my best recollection, some contact was made with the shots that came my way, but in a very short time we lost the match.

The inexcusably stupid part of my gaff was that even at age 20, with no real idea of what too much liquor could do to my coordination, something should have warned me on my own before my getting out on the court – certainly when I was seeing double – that I should get the hell out of there, no matter the consequences.