The 2018 U.S. Open marks the 50th anniversary of the tournament as an “Open” professional tournament, open to pros and amateurs. Arthur Ashe famously won the first edition of this new “Open Era” but as the famous idiom goes “you never remember who finished second.” That year, the runner-up was the great but much lesser known Dutch star Tom Okker. “The Flying Dutchman” was his nick-name and he and Ashe played a thrilling five-set final in 1968, with Ashe prevailing by a 14-12, 5-7, 6-3, 3-6, 6-3 scoreline. Because Ashe was still an amateur player, Okker, despite the loss, was awarded the $14,000 first-prize paycheck.

Okker is Jewish and is featured in the book “The Greatest Jewish Tennis Players of All Time” by Sandy Harwitt, available here https://www.amazon.com/dp/193755936X/ref=cm_sw_r_tw_dp_U_x_C3PFBb43JAT7B and the chapter on Okker is excerpted exclusively below.

The Flying Dutchman

TOM OKKER

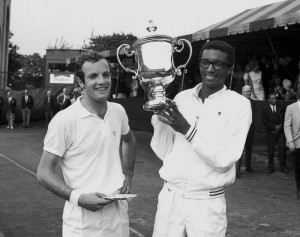

In 1968, Arthur Ashe and Tom Okker — two players still considered to be amateurs — played in the final of the first-ever U.S. Open that would include professional players and offer prize money. Ashe would win, defeating Okker 14-12, 5-7, 6-3, 3-6, 6-3, and collected $15 a day for his achievement. Okker, who had status as a “registered player” — meaning he was an amateur who could collect prize money at certain tournaments — scored the $14,000 top prize check for coming in as the runner-up. Ashe was the first African American man to win a major title. In a country that only recently went through a desegregation process, Ashe’s victory stood out to sports and non-sports fans alike.

That final at Forest Hills, however, is not my most vivid memory of Okker. Very early in my career — as in the first few months — I worked for the late Gene Scott, a former U.S. National semifinalist, who went on to have a multifaceted career in the game, highlighted by being a tournament director and publisher of the now defunct Tennis Week magazine. Gene also was an attorney. It would be hard to find many kids from the New York tri-state area who didn’t receive a start in the tennis business from Gene. As the newly named editor of Tennis Week, one of my perks was that Gene sent me down for the weekend to the Philadelphia tournament, where Okker would team with Wojtek Fibak of Poland to beat Peter Fleming and John McEnroe in a three-set final for the title on Sunday.

I planned on returning to New York after the tournament in the same way I arrived — on the Amtrak train. It provides convenient and pain-free travel between cities on the Eastern Seaboard. When I showed up in the lobby with my suitcase for a ride to the train station — most tournaments are very courteous in providing transportation — Tom Okker also was at the transport desk. When he heard me say I was going to the 30th Street station to get the train back to New York he piped in. He also was heading to New York but was flying. I’m sure I must have frowned as no one from New York would fly to Philly or vice versa. But Okker was moving on from New York so flying made sense. That was when he suggested that instead of taking the train, I should fly with him, as why shouldn’t we have each other’s company on the trip? I guess it sounded kind of decadent to fly between the two places, so I agreed. Plus, LaGuardia was actually an easy place for my mother to come pick me up.

It sounded like a great idea until the moment they were boarding the plane. This was no jet — it was a small propeller number that only had about three steps up to get into and probably had about 12-16 passenger seats. I remember I wasn’t so happy as the plane looked like it arrived straight from World War II service and I must have envisioned the pilot telling everyone it was time to start flapping their arms to keep the plane aloft and not to stop until we landed.

Tom obviously saw my concern. It was at that point he reached to his neck and pulled out a necklace crammed with hanging charms. As he told me that we’d be fine because he had all his good luck medals on, I noticed that two stood out: one was a Jewish symbol and the other representing Christianity. I asked him about it and he explained his father was Jewish and his mother wasn’t and he thought it was advisable to take his luck from all possible sources. He filled in the religious conversation by saying he saw himself as Jewish and had even played at the Maccabiah Games in Israel, winning the singles and mixed doubles titles in 1965.

We arrived in New York safely — it must have been Tom’s good luck trinkets — and that remains the only time I’ve ever flown that route.

Thomas Samuel Okker was born on February 22, 1944 in the Netherlands, a country that was under the occupation of Nazi Germany. The Netherlands had hoped to stay neutral when war broke out in 1939, but in mid-May 1940, the Germans bombed Rotterdam and the next day the country surrendered. The Dutch royal family took refuge in Britain, but the rest of the Dutch stayed behind to deal with being an occupied country. Prior to 1940 there were 140,000 Jews in Holland, but by the time the Netherlands were liberated in May 1945 only 30,000 had survived.

Growing up in a post-war-torn country, it took awhile for life to get back to normal and live beyond the basics. For Okker, It wasn’t until he turned 10 that he was introduced to tennis. When he started winning junior tournaments, Tom thought that pursuing tennis seriously would be fun.

Finding a path to the international tennis circuit, Okker would end up winning 31 singles titles and reaching the final of 24 additional events. He would rank among the top 10 for a number of years with a career high of No. 3 in March 1974. His best Grand Slam result was reaching that 1968 U.S. Open final, but he also reached the semifinals at the other three majors during his career. In 2014, he still sits high on the list of Top 50 all-time Open Era title leaders at No. 24 in the world with his 31 singles trophies.

Okker also was a prominent doubles player and on February 5, 1979, he became the fourth doubles player in the history of the official ATP doubles rankings to become ranked No. 1 — he would occupy the top spot for a total of 11 weeks in his career. He won two Grand Slam doubles titles: at the 1973 French Open with John Newcombe and at the 1976 U.S. Open with Marty Riessen. In all, Okker won 78 doubles titles, which was a record until Australian Todd Woodbridge broke it in 2005. Okker, who was one of the first to frequently use a heavy topspin shot, competed in 13 Davis Cup ties between 1964 and 1981, amassing a 15-20 win-loss record.

When Okker decided it was time to put down his racket in 1981, he became an art broker, first as a founding partner of Jaski Art Gallery in Amsterdam and, in 2005, opened Tom Okker Art in Hazerswoude-Dorp, the town outside of Amsterdam where he lives. Okker’s gallery is all things related to the CoBrA movement of art, which highlights abstract expressionist artists from Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam.

Okker was enshrined into the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 2003.