There is much in the news about the global “Occupy” protests, headlined by the “Occupy Wall Street” protests in Lower Manhattan. If there protests took place 80 years ago (when insider trading was actually legal), then a reigning Wimbledon champion might be in the middle of the ruckus.

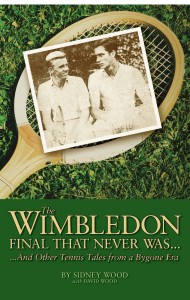

In his post-humously released memoir THE WIMBLEDON FINAL THAT NEVER WAS ($15.95, New Chapter Press, Available here: http://goo.gl/7AWAf) 1931 Wimbledon champion and International Tennis Hall of Fame member Sidney Wood discusses his job on Wall Street the summer after winning the world’s most prestigious title (boy how things have changed!). Wood also reveals how he profited from an “insider trade” before there was even an SEC!

The year was 1931. the stock market was at its nadir, and a 1/8 uptick on a stock was far more important than the services of a newly-crowned Wimbledon champion. Each day, I would rattle into Manhattan from St. James (Long Island) in an old tin Lizzie Ford to seek my fortune, more accurately, in hopes of contributing something to my family’s depression-dwindled income.

After weeks of getting no further than the waiting rooms of numerous brokerage houses, it became increasingly clear that firing, not hiring, was the prevailing way of life on Wall Street. Among the macabre jokes going the rounds was that firms were installing diving boards on their windowsills. Then one day when I called home, there was a message from an older Memphis friend, Brigadier General A.K. Tigrett. The message said that he was in town and would like me to have dinner with him and stay over at the Vanderbilt Hotel (the tennis people’s digs at the time). A.K. was the President of the Southern Tennis Association, as well as the Cottonseed Oil Company of Memphis.

A.K. noticed that I was not my normally ebullient self, and when I told him of my job-hunt frustrations, he immediately said not to worry and that he’d fix me up the next day! So in the company of two of A.K.’s young Ziegfeld Follies charmers, we went out to dine and dance.

The next morning, ring around the collar and all, A.K. took me downtown to meet Dick Hoyt of Hayden Stone, then a major brokerage firm. I was immediately put to work as a runner at the going rate of $8 per week (about $250 in today’smoney). Only those who were around back then could appreciate what it meant for me to bring home my first-ever paycheck. I can truthfully say that it was more rewarding than being presented with Wimbledon’s treasured Renshaw winner’s trophy.

The next summer, the USLTA somehow managed to provide enough expense funds for my Wimbledon defense junket to cover what I’d be missing from working at Hayden Stone. Come the following September when, after a tough loss in the semifinals of Forest Hills, I headed for Long Island and the house of George F. Baker, whose daughter, Titi, had indicated I’d be welcome. Tommy Suffern Tailer, a friend and top golfer (known to intimates as T. Suffering Cats), was married to Titi’s sister Flo. He understood how hard the afternoon’s loss had hit me, and made sure that I was provided a few extra quaffs to assuage my loss.

The next morning with throbbing head, I boarded Mr. Baker’s commuter cruiser for the trip to New York. Mr. Baker headed National City Bank, and my fellow passengers were a half dozen other high-level tycoons. When a huge tureen of scrambled eggs and bacon appeared, I paled, excused myself and managed to survive the voyage.

When we arrived at “my” 25 Broad Street office, who should pull up but Charles Hayden, head of the firm. Mr. Baker introduced us, and in the elevator, when Mr. Hayden asked, “What floor?” and I replied, “Nine”, he exclaimed, “That’s one of mine!” Not more than ten minutes later, I was told to report to the tenth floor where to my astonishment, a desk awaited me with a note that I was now a “Customer’s Man” at the then unheard of munificence of $25 per day! My job seeking sequence sure added credence to the “It’s not what but who you know” adage. (Charles Hayden was also the power behind the Waldorf Astoria funding that got it built.)

About a year later, yet another A.K. favor: He called to tell me that the Gulf Mobile and Ohio Railroad, headed by his brother, I.B., would be paying a whopping $18 in accumulated dividends, on its $50 par value convertible preferred. The stock hadn’t yet moved and I loaded family and everyone up to the hilt at its 38 to 40 sub-par price. Only a couple of weeks later, the entire $18 back interest was paid and the ex-dividend price jumped up to near its $50 par value. The combined back interest and ten or so point stock appreciation netted us close to a 100 percent profit. There was then no Securities & Exchange Commission, and no perception that insider tips weren’t entirely kosher. So, double bless you, A.K.